Restoring

Improving Streams previously dammed, channelized, or impaired.

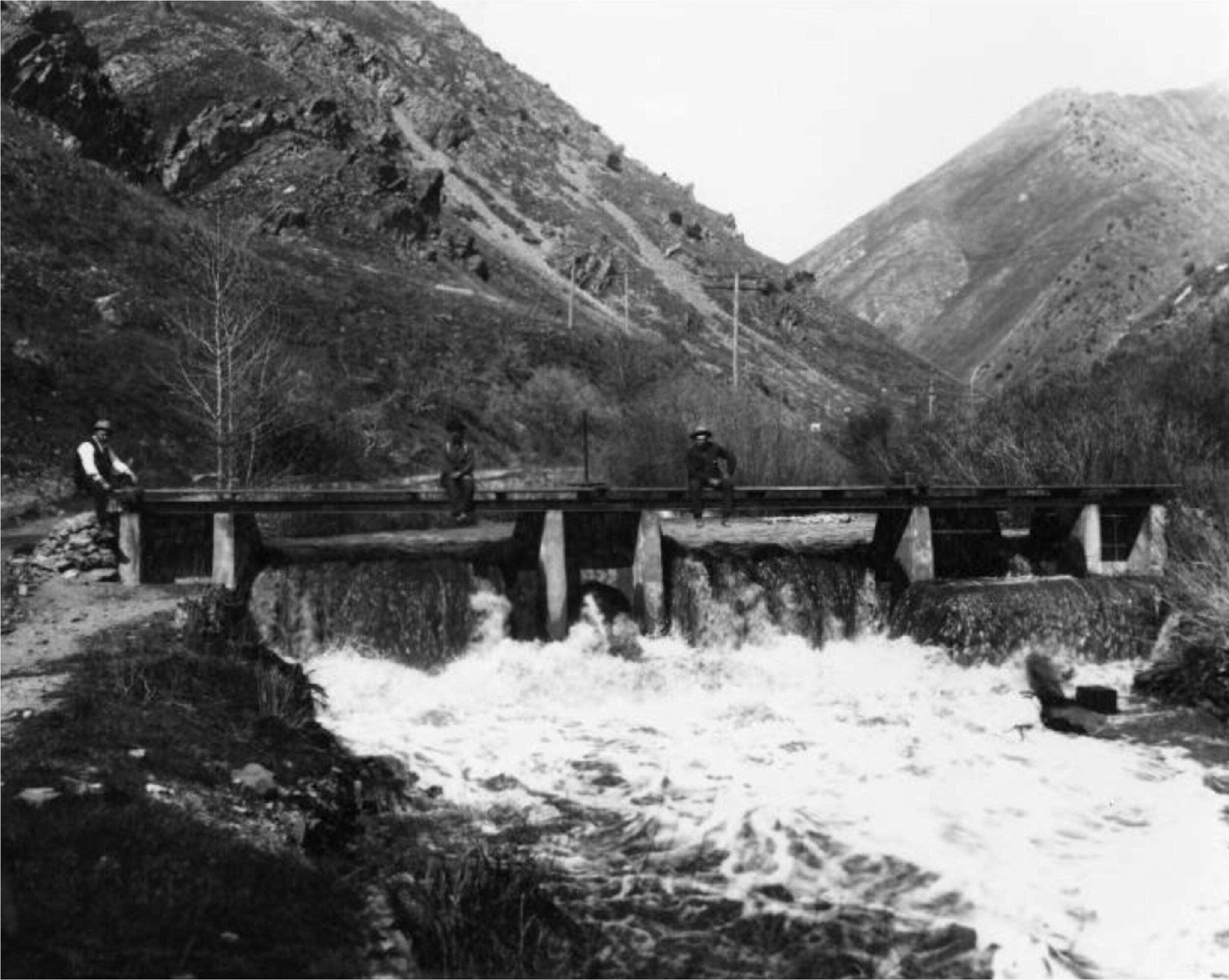

A century of taming and tapping our urban creeks left them in a degraded condition. Industry and development polluted water quality. Creeks were channelized to control flooding. Banks steepened and eroded. [01] Dams and aging infrastructure eliminated fish passage, disjoined wildlife corridors, and reduced access. [02]

Restoration aims to improve health of a waterway and riparian ecosystem. Efforts improve water quality through plantings, bank stabilization, and other green infrastructure. It recreates channel meanders, removes dams, and replaces aging infrastructure. Our urban creeks will become an equitable, innovative, and resilient system of greenway corridors. They will flow across our divides and connect us all to nature in this oasis on the edge of a desert.

Daylighting

Uncovering streams Previously buried in a pipe.

In the early 20th century, as urbanization gripped the Salt Lake Valley, creeks gave way to concrete and asphalt, bricks and mortar. Waterways were diverted from aboveground channels into stormwater pipes underneath our neighborhoods. Gone.

Stream daylighting aims to restore a naturally-functioning waterway and riparian ecosystem—or to the most natural state possible. This depends on factors upstream, surrounding land-use, and the space available. Other forms of daylighting include architectural and cultural. Architectural daylighting brings a stream to surface into an engineered channel, characterized by a concrete streambed and banks. Whereas, cultural daylighting celebrates a buried stream through markers or public art to showcase its historic path. [03]

“Stream restoration is neighborhood restoration.”

Projects

Riparian Restoration

Improving our creeks through daylighting, habitat improvement, and property acquisition.

Community Building

Developing stewardship through events, environmental education, and workshops.

Journal

Our stories from the past & present

Words of reflection from our people, neighbors, and communities. A voice for trees and wildlife. A tongue for the buried and impaired creeks.

Toolbox

Your technical resources

From reports to maps and policy tools to data — the information you care about at your fingertips.

News

The latest updates

From project updates to intriguing articles and historic clippings to inspiring news — notes from the front lines of the transformation of our urban creeks.

Profiles

Our seven canyon creeks

The snowmelt runoff. The green veins that connect our cities. The sustainers of life. Learn the creek facts of the seven major tributaries flowing from the Wasatch Range in Salt Lake County.

The Why

Water & Air Quality

Approximately 87 miles of Salt Lake County’s seven creeks are impaired under the Clean Water Act. An estimated 21 miles are buried in underground stormwater pipes [05]. Culverting speeds up creek velocities, increases erosion, and transports nutrients downstream. Underground streams provide no filtering of air and water through vegetation, both in-river and along streambanks. Natural creeks retain nutrients and clean water quality through streamside vegetation, streambank deposition, and groundwater infiltration [06]. Riparian forests filter air pollutants [07].

Resiliency

Culverts create choke points in the stormwater system. Evidence from flooding in 1983 suggests culverts became obstructed with flood debris, causing $34 million worth of damage County-wide [08]. Whereas, daylighting removes choke points and slows water velocity, compared to smooth concrete culverts, through meanders and rocky and vegetated banks. Streams, especially with the inclusion of a floodplain, increase groundwater infiltration and storage [03]. Groundwater can become an increasingly important source of drinking water with climate change uncertainty and a growing population.

Habitat

Salt Lake is a critical stopping point for neo-tropical migratory birds. Riparian vegetation supports the nesting and breeding of these world-travelers. Additionally, an estimated 80 percent of Utah’s species rely on riparian ecosystems. However, these habitats represent a meager 1.2 percent of the City’s total land area [02]. Daylighting creates new riparian habitat to support Utah’s biodiversity, decreases habitat fragmentation and forms wildlife corridors, and improves fish passage.

Quality of Life

Creeks add visual attraction, create a sense of place, and mask the sounds and sites of the urban environment. Residents gain restored access to nature, critical in the development of children and the mental and physical wellbeing of adults [09]. They provide gathering space for picnics, events, festivals, and interaction. Trees and streams cool air temperatures.

Economics

Daylighting facilitates surrounding development, and increases property values and business revenues. An $18-million daylighting project, in Kalamazoo, MI, generates $12 million in revenue each year through festivals. Many communities are finding daylighting to be more cost effective compared to the lifecycle costs of replace aging infrastructure [03].

Education

Creeks become living laboratories for nearby schools. Students can study the benefits of daylighting through water quality testing and biological surveys.

Recreation

Streamside pathways and commuter trails create active transportation and recreation connections. On newly uncovered creeks, anglers can fish for Utah’s indigenous trout, the Bonneville cutthroat. Access to trails and recreation increase public health. Trail users save over $500 in reduced medical care due to increased physical activity [10].

Case Studies

A global phenomenon

From Kalamazoo, Michigan to Seoul, South Korea—from Zurich, Switzerland to Salt Lake City, Utah, communities are resurrecting, and giving life, to lost streams. The green veins of our cities are returning. Wildlife is reappearing—people are enjoying.

History

Our stream story

Some 60 to 90 million years ago, rock layers folded, compressed, and thrusted along the Wasatch Front to form seven major canyons in Salt Lake County [01]. Out of each canyon flows melted snow and runoff to the Jordan River and onto the Great Salt Lake. From Exploration of the Great Salt Lake of Utah [11]:

“The site for the city is most beautiful: it lies at the western base of the [Wasatch] Mountains… for twenty-five miles extends a broad level plain, watered by several little streams, which, flowing down from the eastern hills, form the great element of fertility and wealth to the community.”

Indigenous peoples hunted, fished, and gathered here. Early colonial settlers used the canyons as pathways to the Salt Lake Valley and beyond, as well as a source of water and industry. This shaped the waterways. Pollution from industry and development degraded water quality. Creeks were channelized as they entered the Valley to control flooding. Banks became steep and eroded [01]. This led to the burial of creeks, dubbed a nuisance, in the early 20th Century.

An estimated 87 miles have impaired water quality and 21 miles are culverted underground. Even then, residents saw the damaging outcome. An article from the time [12]:

“To hide completely the flowing water within a conduit and to make of the street a stretch of ordinary pavement would be to throw away opportunity for which many cities would gladly pay a million dollars.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Flooding +

Will this increase flooding?

Urbanization markedly increased flooding during the 20th century. Imperviousness is categorized by changes in land-use that do not allow for precipitation to soak into the ground, such as roads, sidewalks, and buildings. Rather, water runs off the surface of our cities and into the stormwater system.

Historic 100-year floods double in size with 30 percent imperviousness [01]. Salt Lake County’s average impervious area is estimated at 33 percent [02]. Channeling and piping streams transferred impacts downstream, increasing flooding and erosion in our west-side communities along the Jordan River. Smooth concrete pipes and straightened, deepened streams speed up water velocity.

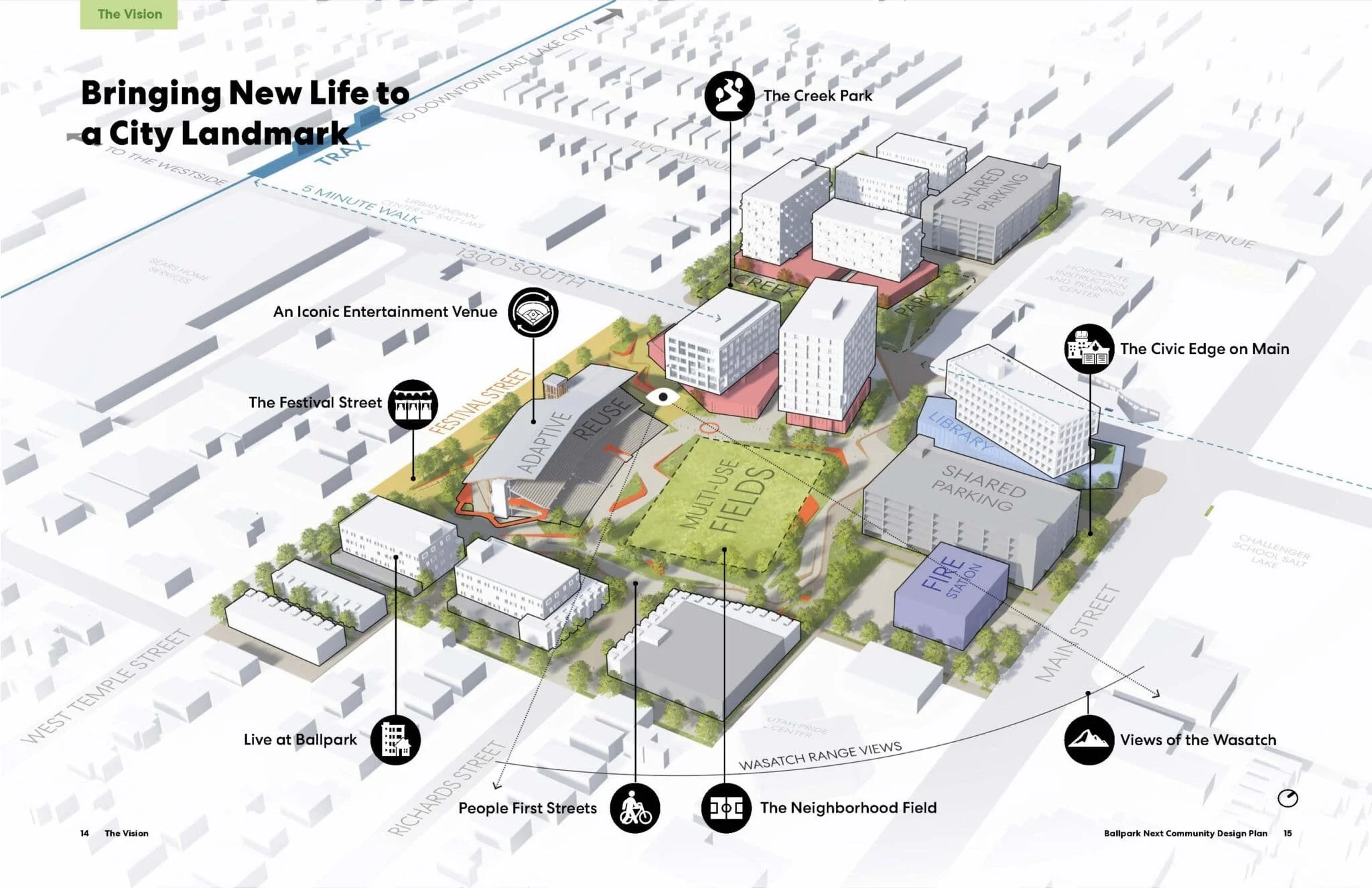

Culverts create choke points in the stormwater system. Evidence from flooding in 1983 suggests culverts became obstructed with flood debris, causing $34 million worth of damage County-wide [03]. In 2017, a 200-year precipitation event overwhelmed Salt Lake City’s stormwater system in areas surrounding our underground creeks, primarily the Ballpark and Sugar House neighborhoods, as well as the Jordan River corridor. Parleys Creek overtopped its culvert at Hidden Hollow, leaving five feet of water in the basement of the historic Sprague Library. Over 1,000 books ended up in the dumpster. Damage was estimated at $1.5 to $2 million, and the branch was closed for four months [04]. The Salt Lake City Fire Department estimated 100 homes were flooded. Over 5,000 customers experienced power outages. Utah Transit Authority reported delays as tracks and roads were submerged [05]. Salt Lake City School District estimated $2 to $3 million of damage at four schools [06].

Uncovering and restoring streams slows water velocity through meanders and rocky, vegetated banks. Especially with the inclusion of a floodplain, groundwater infiltration and storage are increased [07]. Removal of culverts alleviates choke points, and can replace under-capacity or deteriorating culverts. Daylighting of Arcadia Creek, replaced one such culvert. Once an area that experienced frequent flooding, the channel now protects against the 500-year flood. Floodplain maps were redrawn post-project, and businesses no longer pay for flood insurance [08]. Daylighting streams is a key link in the green infrastructure network to retain, treat, and absorb stormwater where it falls.

Daylighting will be done only if it decreases flooding risk. Stream channels will carry the same or greater capacity of the culvert it is replacing. Another option is to preserve the existing stormwater infrastructure to convey high flows. The creek then serves as additional capacity.

Sources

- Hollis, The effect of urbanization on floods of different recurrence interval (1975).

- Salt Lake County, 2015 Salt Lake County Integrated Watershed Plan (2017).

- Hooton, Memorial Day Weekend 1983 (1999).

- Stevens, Sugar House library re-opens after devastating flood that destroyed thousands of books (2017).

- Williams, Waist-deep water floods homes, cuts power in Salt Lake (2017).

- Mims, ‘Torrential’ thunderstorms flood East High School, SLC’s Sprague Branch, Wasatch Front intersections (2017).

- Trice, Daylighting Streams (2016).

- Pinkham, Daylighting: New Life for Buried Streams (2000).

Pests +

Will this increase the risk of West Nile virus?

Stream daylighting involves careful engineering. Creeks are designed to keep water flowing, and this prevents the breeding of mosquitoes. They typically need about ten to 14 days of standing water to complete their life cycle [01]. With the introduction of riparian habitat, mosquito predators--birds, dragonflies and other insects, amphibians, fish, and bats—increase. In addition, Salt Lake City and South Salt Lake Valley Mosquito Abatement districts monitor and control mosquito populations throughout the Salt Lake Valley, including our urban waterways.

About 80 percent of those infected with West Nile virus do not develop symptoms--less than one percent develop a serious illness [02]. The Culex species is the main vector for West Nile virus [03]. They are highly opportunistic in breeding. Often, they seek standing water around our cities, including our storm drains and culverts.

Mosquitos are best addressed in our developed areas. Ways to address mosquitoes [04]:

- Unclog roof gutters;

- Empty unused swimming pools or any other standing water;

- Change water in birdbaths and pet bowls regularly;

- Remove old tires or unused containers that hold water; and

- Clean and stock garden ponds with mosquito-eating fish or mosquito dunks.

Does it increase numbers of other pests?

Rodents are a common mammal along our creeks, and become pests when they move to adjacent properties. As with mosquitos, increasing riparian habitat increases natural predators. The best way to prevent infestations is to remove the food sources, water, and items that provide shelter around your home.

Sources

- American Mosquito Control Association, Life Cycle.

- Utah Department of Health, Utah Weekly West Nile Virus Surveillance Update (2019).

- Vector Disease Control International, West Nile Virus (2020).

- Utah Department of Health, West Nile Virus Fact Sheet (2018).

Safety +

Will uncovering our creeks become a safety issue?

As with all natural areas, there is inherent danger and risk of accident. Our streams are dynamic systems that should always be respected; not treated as swimming pools or fountains. Creeks should be enjoyed from a distance and designed with safety in mind. Steep banks should be made gradual (with the added benefit of preventing erosion and stabilizing the soil). Fencing and other barriers, intended to keep people out, often do the opposite. They prevent people from escaping dangerous situations.

From 1999 to 2018, per 100,000 Utahans, less than one person dies from drowning per year, many in swimming pools and bathtubs. Motor vehicle deaths: eleven [01]. The roads that intersect our communities are much more dangerous than the creeks that connect us.

Channelized and culverted creeks create dangerous safety hazards in our communities. Children and adults can get swept away in high-velocity, channelized waters. They can get sucked in pipes and pinned against grates, energy dissipaters, and other infrastructure. According to the Albuquerque Metropolitan Arroyo Authority, Albuquerque County estimates a drowning occurs in its streams every two to three years. With 50 miles of concrete-lined channels and 100 miles of soft-lined ones, a much higher proportion of deaths occurred in the concrete-lined streams [02]. By uncovering and restoring creeks, water velocity is slowed and people are better able to escape dangerous situations.

Daylighting projects have a good safety record. Blackberry Creek was uncovered in a schoolyard, replacing a dilapidated and dangerous playground. Ann Riley explains [03]:

“The Blackberry Creek daylighting project sent the message that these kinds of projects were safe, even in school grounds, even if the creek was as much as 20 feet below existing ground elevation, and even if the side slopes were steep 2-to-1 and 1-to-1 slopes… [It] was well loved, used often, and played a central role in the science curriculum at the school. There are no reports of injuries or accidents at the creek, which is certainly a safer play environment than the playground it replaced.”

Sources

- Utah Department of Health, Utah Death Certificate Database (2018).

- Riley, Restoring Streams in Cities (1998).

- Riley, Restoring Neighborhood Streams (2016).

Water Quality +

Does uncovering our streams jeopardize water quality?

Approximately 87 miles of our seven creeks are impaired under the Clean Water Act. An estimated 21 miles are buried in underground stormwater pipes [01]. Water quality impairments include aquatic habitat condition, E. coli, heavy metals, pH, low dissolved oxygen, temperature, and total suspended solids. [02]

Placing streams in underground culvers eliminates ecological processes. Without vegetation, streams do not filter air and water pollutants, both in-river and along streambanks. They no longer deposit sediments on banks. Pollutants, nutrients, and sediments are transferred downstream. Culverting carries impairments eight times further downstream, and reduces nutrient retention by 39 percent [03]. Harmful algal blooms develop as a result, and affect downstream low-income communities along the Jordan River. They are a health risk for children and pets, a detractor of recreation and agriculture, and an ecological disaster for wildlife [04].

Conversely, daylighting streams revitalizes ecological systems. Sunlight breaks down bacteria [05]. Streamside vegetation cleans water pollution through nutrient retention, streambank deposition, and groundwater infiltration [06]. Thereby, harmful algal blooms are mitigated by removing pollutants at the source—before concentrating downstream. Riparian forests filter air pollutants and cool temperatures [07].

E. coli contamination caused frequent beach closures at Indiana Dunes State Park. The culvert, containing Dunes Creek, was an incubator for the bacteria. The culvert was removed and the creek uncovered--replacing a surface parking lot [08]. Sunlight, vegetation, and micro-organisms reduced E. coli levels. Fewer beach closings (if any) are anticipated, increasing revenue for the park [09].

Urban runoff was increasing sediment loads and degrading water quality in downstream Thornton Creek. Redevelopment on a surface parking lot prompted daylighting. A series of swales and pools slow and treat stormwater from the adjacent 680-acre drainage. Sediments and pollutants are settled out and retained by wetland vegetation, which provides habitat for birds, insects, and other wildlife. The facility will achieve a 40 to 80 percent removal of total suspend solids (sediments and pollutants) [10].

Open streams are more easily monitoring and managed. After uncovering Blackberry Creek, it was found the creek was being polluted with sewage. Previously, this sewage was being sent to the San Francisco Bay, unbeknownst to all. The issue was quickly addressed once nearby elementary students lobbied local officials [11].

Sources

- Seven Canyons Trust, Creek Channel Alignment Data (2018).

- Salt Lake County, 2015 Salt Lake County Integrated Watershed Plan (2017).

- Pennino, Effects of urban stream burial on nitrogen uptake and ecosystem metabolism (2014).

- United States Center for Disease Control & Prevention, Harmful Algal Bloom Associated Illness (2020).

- Pinkham, Daylighting: New Life for Buried Streams (2000).

- Salt Lake County, Stream Care Guide (2014).

- Buchholz, Urban Stream Daylighting Case Study Evaluations (2007).

- Trice, Daylighting Streams (2016).

- Hohman, Daylighting in the Dunes (2007).

- City of Seattle, Thornton Creek Water Quality Channel Final Report (2009).

- Riley, Restoring Neighborhood Streams (2016).

Dewatering +

Will our creeks run dry during certain months?

Our creeks are dynamic, natural systems. Along a stretch of creek, reaches are gaining, meaning groundwater is added to the flow through springs and seeps. Others lose flow through groundwater infiltration. Streams can become dewatered (a stream without flowing water) through a losing reach and receive water through a gaining reach.

Portions of our creeks are artificially dewatered. This is caused by water rights for irrigation, hydropower, and drinking water. Diversions seasonally dewater portions of both Big Cottonwood and Little Cottonwood creeks. From November to March, half of Big Cottonwood Creek is dewatered through the Valley. Little Cottonwood Creek has little flow from July to March, becoming fully dewatered in dry years. Canals bring in some water to these creeks from the upper Jordan River and Utah Lake. This has seriously degraded water quality and the riparian ecosystem [01].

In our Basin and Range geography, perennial streams were historically rare [02]. Urbanization concentrated flow in our streams through stormwater inputs and runoff on impervious surfaces, like roads, parking lots, and buildings. Due to a lack of historical data, we do not know the pre-urbanization creek conditions. Lack of historic mapping for certain creeks, like Red Butte and Emigration creeks, may have meant these were intermittent or dry during certain seasons. Flow came during snowmelt runoff and precipitation events. Whereas, larger streams would have been perennial--flowing throughout the year.

We believe in celebrating natural, dynamic streams. Creeks will reflect their existing conditions. Stormwater inputs can be added to increase stream flow. This improves the quality of stormwater by retaining nutrients and filtering pollutants through streamside vegetation, streambank deposition, and groundwater infiltration.

Sources

- Salt Lake County, Stream Care Guide (2014).

- Penn State University, Intelligence Analysis, Cultural Geography, and Homeland Security: The Basin and Range Subregion (2020).

Property Ownership +

Who owns the land?

It is a patchwork of private and public land. Our streams flow through or underneath residential areas, commercial and industrial areas, and public lands, like parks and open space. Large stretches of the underground portions flow underneath roads.

What can I do if I have a stream flowing underneath my property?

What an opportunity! There are several options to daylight the creek through your property. First, email info@sevencanyonstrust.org to let us know you are interested in the idea. We will work with you to find the best option.

Barriers +

Stream daylighting is expensive. Why should we pursue it?

Yes, daylighting is typically a complex, labor-intensive, and costly process. Expertise is required in engineering, excavation, and landscape design. Often, earthmoving and removal of soils is the most expensive part, especially when working around contamination. According to the Rocky Mountain Institute, the daylighting process costs $1,000 per linear foot on average [01]. Costs vary depending on the existing land condition, if property acquisition is needed, and the extent of additional amenities added, such as benches, lighting, trails, and other park amenities [02].

Costs are reduced using volunteer labor and in-kind donations for some of the work. If soil can be used on-site, removal and disposal is not necessary. Construction companies can donate earthmoving services, nurseries: planting stock, or businesses: volunteer labor. Conservation corps can be used to reduce labor costs, while training future restoration experts. For perspective, according to the American Road & Transportation Builders Association, it costs $1,900 per linear foot to construct a new four-lane highway [03].

As illustrated by Arcadia Creek, stream daylighting can be a cost-effective investment when evaluating the full range of benefits. City engineers found uncovering the creek would be cheaper than excavating, replacing, and reburying the deteriorating culvert [01]. The life cycle costs associated with the construction, maintenance, and replacement of underground culverted systems often prove more expensive, or only marginally less, than uncovering the stream (without the additional benefits of daylighting).

This $18-million public investment in Kalamazoo leveraged a total of $200 million in private development, surrounding the project. Property tax revenues in the area have increased annually from $60,000 to $400,000 to pay back the bonds. The Arcadia Creek Festival Place hosts five regional summer events, generating an estimated $12 million a year [01].

No other project highlights the business potential of streams than San Luis Obispo Creek. During restoration, businesses were encouraged to open secondary entrances facing the stream to activate the area. These have since become primary entrances facing a walkable plaza and creek--the heart of the City’s downtown. At first apprehensive, businesses attribute rises in revenue to the restoration [04]. Surrounding vacancy rates have decreased from 60 percent to zero, according to the San Luis Obispo Chamber of Commerce [05].

Highly visible daylighting projects can increase community consciousness about underground streams. A knowledgeable community supports stream care and stewardship. This can spark additional stream restoration programs and funding sources.

What are other barriers to daylighting?

Due to the high cost, strong community support and political will is needed. The first step is engaging the community surrounding a potential project. Many residents are unaware of buried streams in their neighborhood. Communication, education, and engagement ensure more meaningful results.

The second step is to find governmental champions. These leaders help move the project through the bureaucracy of local governments, and ensure the project is considered in planning, budgeting, and grant opportunities. With community and governmental support, research and fundraising can begin.

Sources

- Pinkham, Daylighting: New Life for Buried Streams (2000).

- Trice, Daylighting Streams (2016).

- American Road & Transportation Builders Association, Frequently Asked Questions (2020).

- Hoobyar, Daylighting and Restoring Streams in Rural Community City Centers (2002).

- Sparks, Giving the downtown area an identity (2015).

Sources

To spark your further research

Carlstrom, The History of Emigration Canyon (2003).

BIO-WEST, Inc., Salt Lake City Riparian Corridor Study: City Creek Management Plan (2010).

Trice, Daylighting Streams (2016).

Riley, Restoring Neighborhood Streams (2016).

Seven Canyons Trust, Creek Channel Alignment Data (2018).

Salt Lake County, Stream Care Guide (2014).

Klapproth, Understanding the science behind riparian forest buffers (2009).

Hooton, Memorial Day Weekend 1983 (1999).

Louv, The Nature Principle (2011).

Wang, A cost-benefit analysis of physical activity using bike/pedestrian trails (2005).

Stansbury, Exploration of the Great Salt Lake of Utah (1852).

Deseret News, City Creek Should Be Preserved (1921).

Historic Photos: Utah State Historical Society.