Salt Lake Valley creeks to shoulder heavy spring runoff

Authored by Amy Joi O’Donoghue

Source: Deseret News

An article detailing the high snowpack and flooding potential in 2011. It outlines the flood mitigation and stormwater system underneath Salt Lake City.

Seven main canyon creeks on the east side of the Salt Lake Valley convey the water that melts out of a mountain snowpack. This year's runoff poses a particular challenge as the snowpack is 191 percent of normal as of early May.

Managing how those creeks will get that much water safely to the Jordan River is much like directing motorists in a horrible traffic jam; there's only so many places those cars can go, and the traffic officer feels like pavement is running in short supply.

The good news is since 1983 — the year of the big flood that is on everyone's mind — a lot of little side streets have been built to help move things along more smoothly.

Jeff Niermeyer, Salt Lake City's director of public utilities, is optimistic that two debris basins put in at the mouth of City Creek Canyon will prevent what happened in May 1983, when the underground City Creek culvert at North Temple and State Street became clogged.

With the rushing water having nowhere to go, the high flows pooled with such force manhole covers blew off and State Street turned into a river.

Going from north to south, Salt Lake's urban creeks — City, Red Butte, Emigration and Parleys — flow out of the canyons and at some point are channeled underground.

"It's been that way for over 100 years," Niermeyer said. "Whatever political decisions were made back then to bury the creeks were likely done for a host of reasons — to control flooding or provide for more developable land."

On the extreme eastern side, city residents can enjoy the ambiance of a riparian waterway on their property.

It does, however, come with risks.

"As the city has learned over the decades, these little babbling brooks can often turn into raging torrents," Niermeyer said. "We have to devise systems to pass them through the urban core with a minimal amount of flooding."

City Creek is conveyed through a 66-inch culvert that eventually turns into an 84-inch boxed culvert along North Temple that dumps into the Jordan River. A secondary drainage to divert some of the water starts at North Temple, conveying it to 200 South and over to the Jordan River.

Both Red Butte and Emigration creeks converge at Liberty Park at 1300 South. Niermeyer said a $16 million storm drainage system was installed in 2006 that pulls half their flows over to 9th South as a way to relieve pressure in a high-water year such as this.

Parleys, like Red Butte and Emigration, is conveyed underground at 1300 South, but not before Little Dell Reservoir can capture up to 20,000 acre-feet of water. That reservoir is another improvement put in since 1983, when all that existed in Parleys Canyon was Mountain Dell with a capacity of 3,000 acre feet.

While all of Salt Lake City's creeks are at some point channeled underground, occasionally a portion of the flow is brought up to be what is called a "water feature."

At the LDS Conference Center, City Creek water — but not the creek itself — is transformed into a waterfall. A little farther to the east, a pump delivers just under 900 gallons of City Creek water per minute to form a faux creek at North Temple and State Street.

Niermeyer said there are plans to have some facsimile of City Creek running through its namesake multibillion dollar development by the LDS Church in the heart of downtown Salt Lake City.

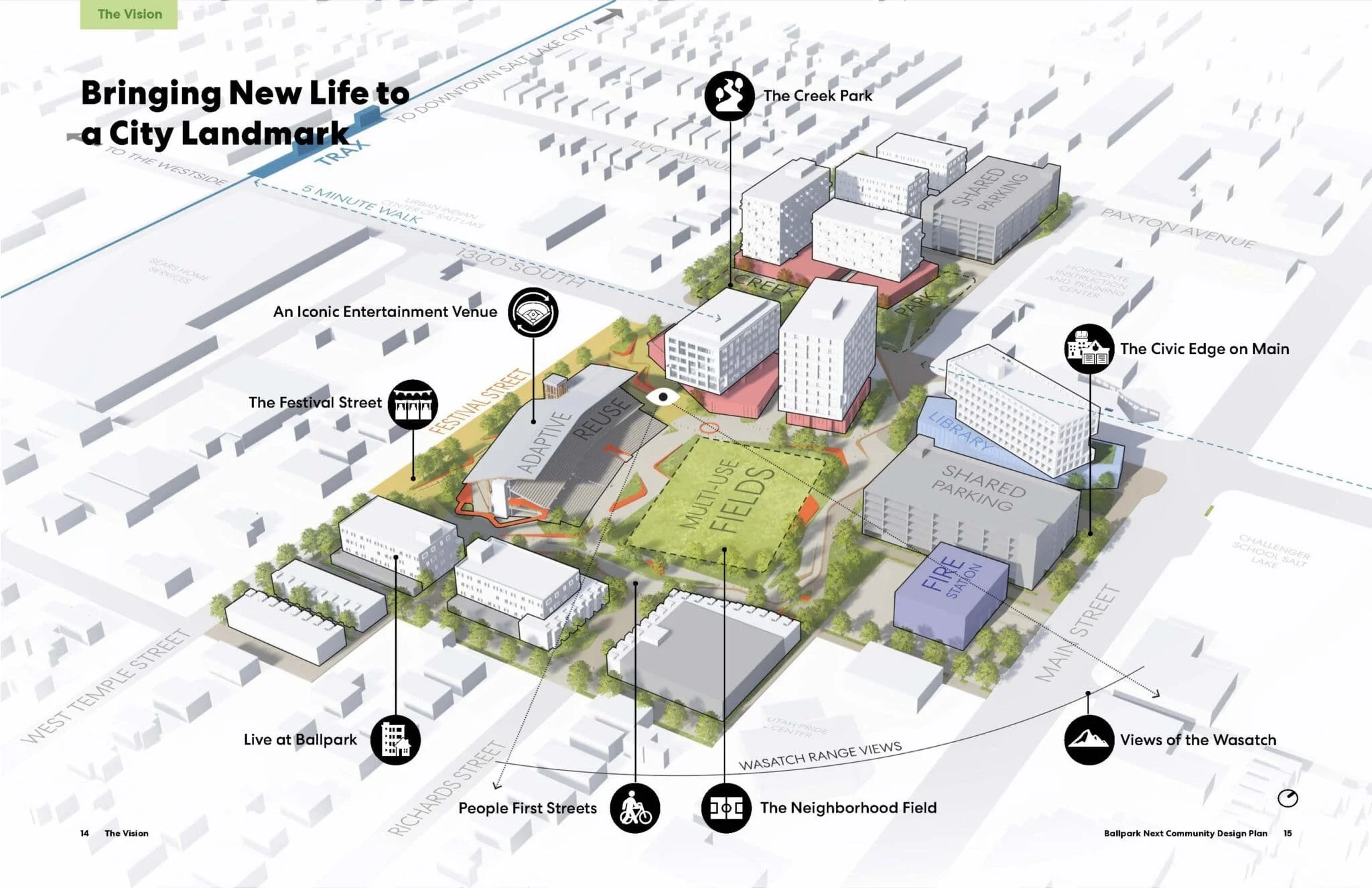

There are also plans to develop a creek-style feature off City Creek in the EUCLID redevelopment planned for the neighborhoods between about 600 West to 1000 West at 50 South. Part of the idea is to have the creek enhance a trail system along the Jordan River and also install additional runoff capacity at Folsom Street, Niermeyer said.

While the city's four riparian waterways are "fairly benign and tame streams," Niermeyer said a big flood year like 1983 can transform them into a menacing threat if not controlled.

"We have these wet cycles that go into drought, wet cycles and then drought again. In those dry cycles, people can forget the lessons they learned in the wet years."

Both Niermeyer and Brent Beardall, engineering manager for Salt Lake County, said there has been talk over the years about bringing up some of these Salt Lake City creeks, particularly City Creek.

"It would be very expensive, and where are you going to put it?" Beardall questioned. "It would be a difficult thing to do."

Farther south in the Salt Lake Valley, the main creeks are Mill Creek, Big Cottonwood Creek and Little Cottonwood Creek, which have runoff efforts augmented by smaller waterways such as Bells Canyon, Big Willow and Corner Canyon creeks, to name a few.

All flow mostly above ground as natural waterways and end at the Jordan River.

On all of these creeks in the valley there are diversions — water routed through exchanges to irrigation ditches or canals. There are two large canals on the east side of the valley, and four major ones in the western half, where four major creeks typically don't pose flooding problems due to runoff.

The flooding threats on the west side of the valley come with summer rainstorms that have the potential to overwhelm channels and the elaborate storm drain systems.

West Jordan, for example, has spent more than $8 million in improvements over the last decade to Barney Creek, which runs through an open channel and then at one point is piped. Just before it discharges into the Jordan River, it flushes through a man-made wetlands basin that helps capture urban contaminants.

Bingham Creek, while well-defined, handles canal overflows and in high-flow years would have the potential to wash over green space at West Jordan's Teton Park before it ends at the Jordan River.

At the Jordan, a surplus canal at 2100 South takes water off the river to deliver to the Great Salt Lake.

That diversion, Niermeyer said, helps the river make room for the water that is going to drain into the river in high runoff years from City Creek, Red Butte, Emigration and Parleys creeks.

Over the years, multiple improvements have been made in flood control infrastructure as the result of the 1983 floods.

Beardall said a $33 million bond funded much of that, and with debris basins that exist at Big and Little cottonwood creeks and Corner Creek.

Rose Creek on the western side of Salt Lake County was extended to run all the way to the Jordan River and millions have been spent to widen the above ground creeks and fortify their banks.

"We have continued to work on the channels to improve them," Beardall said. "Having said that, it doesn't mean we are bullet proof."