Rivers Revisted

Authored by Jane Lyon

Source: Catalyst Magazine

An article exploring the story of our organization from its origins at the University of Utah to a nonprofit—and beyond. It highlights our Seven Creeks Walk Series as a way to get more involved in our goals.

In the spring of 2014, Professor Stephen Goldsmith, former Salt Lake City Planning Director, Artspace co-founder and director of the Center For the Living City, welcomed into his University of Utah classroom the fresh minds of that semester’s Urban Ecology and Planning Workshop. On the first day, he laid out this issue for the students: what to do about all the underground creeks in Salt Lake City.

Salt Lake’s residents have had a longstanding conflicted relationship with the seven creeks that flow from the Wasatch Mountain’s seven main canyons— City Creek, Red Butte, Emigration, Parleys, Millcreek, Big Cottonwood and Little Cottonwood. When Mormon pioneers traversed Emigration Canyon on the final leg of long and difficult trek to find their mecca and Brigham Young proclaimed, “This is the place,” he was looking over our pristine valley surrounded by a great protective wall of mountains and watered by seven blue veins of life. Those creeks are all tributaries of the artery now known as the Jordan River whose rich plains and creek beds provided for our earliest pioneers the essentials for life in this high and hostile desert.

But as more settlers arrived and the land became more urbanized, people had to mitigate the annual flooding that threatened what had become a downtown area. Burying the creeks under cement and funneling them through pipes became a social imperative. In 1914, a Salt Lake Telegram article praised the burial of City Creek as it protected the water supply and prevented accidental drowning. By the 1980s, 21 miles of our valley’s creeks were buried.

If you were around in May of 1983, you certainly remember “Deluge Sunday,” as The Deseret News called it, when 1,000 homes were flooded and 200 to 400 people were forced to evacuate. The overflow of snowmelt first showed itself at the mouth of Emigration Canyon. Visible flooding appeared along 1300 South where the Emigration, Parleys and Red Butte creeks converge underground. But they were not staying underground. Mayor Ted Wilson called for the floods to be contained and community members began sand bagging the west side of State Street along 1300 South to protect downtown. This would be the last time our city saw the Jordan River tributaries above ground. However, this would also trigger the first time that citizens began to question the efficacy of burying our natural creeks. A group of people began discussing the feasibility of bringing up the creeks, now called “daylighting.”

The term was coined in Berkeley, California in 1986 and since then, Berkeley has been a champion in daylighting waterways. Hydrologically speaking, it is always better for waterways to be above ground as a part of the natural biome.

City Creek, which not more than two decades ago flowed under a surface parking lot owned by the LDS Church, is the first and only successful daylighting project in Salt Lake today. It is a beautiful place that, were it left undone, would still be suffocating under a square of hot asphalt. Hidden Hollow, a restoration project in Sugar House, has a similar happy story. In 1990, a couple of elementary students discovered a littered, long-neglected stream channel near their school. They tackled the project of cleanup and restoration, organizing themselves as the KOPE Kids (Kids Organize to Protect the Environment) in the process. They worked so fervently that Utah Open Lands created a conservation easement to protect the area in perpetuity. Some believe this open space isin part responsible for the flourishing of businesses and restaurants in Sugar House. What we are learning is that engaging in restoration of natural open spaces is good news for the land owners around that area. So, what if we could use this kind of thinking in the less affluent neighborhoods of Salt Lake City?

A certain Stephen Goldsmith quote always echoes through the environmental students’ conversations at the University: “Make the invisible visible.” Throughout the semester of Professor Goldsmith’s 2014 Ecological Planning class, the students took his question and researched, photographed and made Google Earth flyovers to track the creeks on an aerial scale, all with the goal to create a future vision of an above-ground water system.

As the semester wound down, five students stuck around to refine the idea and New York native Brian Tonetti and Salt Lake native Liz Jackson created what they call 100 Years of Daylighting. Their vision is, through grants and partnerships, to acquire the land holding the rest of Salt Lake’s original creek beds and restore beneficial ecology into our neighborhoods.

After receiving an Outstanding Achievement award for their plan from the Utah American Planning Association, Tonetti and Jackson began pursuing 501c3 status. Thanks to financial help from their parents, the project finally received non-profit status in April of last year.

Tonetti and Jackson make up the Seven Canyons Trust (SCT) team, backed by an intern and volunteers. Their first goal is simply raising awareness of what remains underground. Eventually, of course, they aim to restore local ecology through daylighting projects and bring nature closer to home, but until then they are focusing on interventional activism by painting simple blue creek lines over parking lots and cement sidewalks to illustrate where for the hidden creeks flow. This type of artistic activism helps our community envision what it could be, making the invisible a little more visible. The Seven Canyons Trust also invites students and residents of all ages to engage in the Seven Creeks Walk Series, a walking conversation along the creek lines in which people share insights, experiences, history and facts about the creeks.

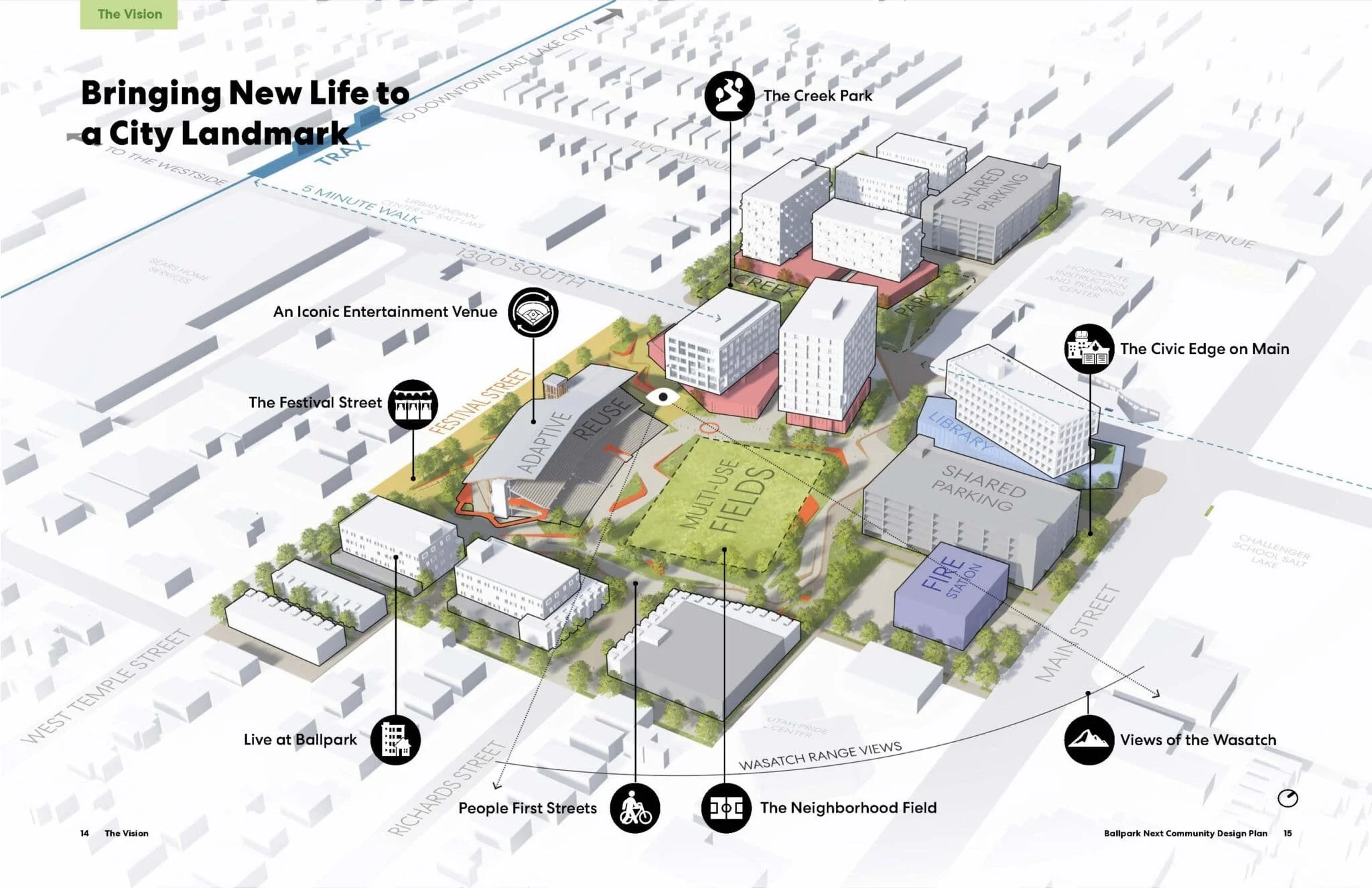

Seven Canyons Trust’s first new daylighting project may soon get underway at the intersection of 1300 South 900 West, in cooperation with the Glendale Community Council and with funding from Salt Lake City and the Jordan River Commission. Other main partners are the Center for the Living City and ArtsBridge America. The intended project will remove an old parking lot and a burned-out, abandoned house over a confluence section of the Parleys, Emigration and Red Butte Creeks. It could be just the first step in revealing and re-visualizing our city’s blue veins.

Jane Lyon is a senior in environmental and sustainability studies at the University of Utah, a former CATALYST intern and an intern for the Seven Canyons Trust. She also co-produces CATALYST’s Weekly Reader.