River of Dreams

Authored by Benjamin Wood

Source: City Weekly

An article navigating the transformation of the Jordan River with emphasis on the Three Creeks Confluence. This project is daylighting three underground creeks as they flow into the Jordan River in Salt Lake City, UT.

A long-buried Jordan River confluence sees the light of day—giving more reasons to love this urban waterway

In 2017, my family moved from Sugar House to Poplar Grove, and I fell in love with the Jordan River.

We had met before; I don't recall exactly when. It was the early two-thousand-teens, I was bored, and I put my mountain bike on my Subaru and *drove* west to check out the trail along the river that someone had mentioned at a party or something.

I remember it being very hot and dry, and I got a flat tire. I maybe rode for a mile?

But in the summer of 2017, I moved to the west side. I ran the Jordan River trail at first, then biked, and there was always more trail to go. And then I was taking the trail to work and to movies with my wife and to the grocery store for my son's frozen burritos because it was just a nicer way to get where I was going.

The parkway trail was formally completed in the fall of 2017. They had a free 5K to kick off the opening of a pedestrian bridge that now spans from 200 South to North Temple. It was fun. I got a T-shirt!

I remember thinking at the time that I needed to write an article. The idea of a continuous trail from Utah Lake to the Legacy Parkway had been around since long before there was such a thing as the Legacy Parkway. An untold number of people did an untold amount of unsung work over decades to make that trail possible.

But it didn't really stop with the trail. In three short years, I've witnessed firsthand the nonstop pace of improvements along the parkway. You get a new bridge! You get a mileage marker! You get weed removal! You get a charming community mural! You get a seemingly endless chain of regional parks and nature preserves! Enjoy, urban explorer!

The parkway trail isn't the story anymore. It's finished. It's far from perfect but as of this moment, it is safer to walk or bike on the parkway than it is to walk or bike on State Street. Go ahead, check the scoreboard.

Today's article is about the river, because everything flows into it. Literally. And because there's some cool stuff happening that I'd like to tell you about. And because I finally saw it from a kayak.

Will There Ever Be a Swimming Hole?

It's raining when I meet Tyler Murdock at the Three Creeks Confluence, a cozy spot along the Jordan River that sits a stone's-throw from the intersection of 1300 South and 900 West.

I ride my bike because I'm that guy, which means I arrive at my first pandemic interview dripping wet and shivering. But Murdock, too, has his hood pulled up and a mask on his face, looking like the Unabomber, and that's just how things are now, I guess.

Murdock is a project manager with Salt Lake City, and he's showing me the new river park and plaza under construction at Three Creeks. It's a big endeavor, with one bridge already on the ground and another on the way.

We look out over the water, and I geek out as Murdock paints me a word picture of what the park could become after it formally opens this fall. I imagine kayakers pulling their boats into and out of the water while clusters of students on a field trip skip stones and anglers cast lines from the observation bridge that will soon span the confluence.

"There's not a lot of places where you have that direct connection to the river," Murdock says. "The river is often hidden because most of the access we have to it is from the parkway trail. In some places you can't even visually see the river—you wouldn't even know it's there."

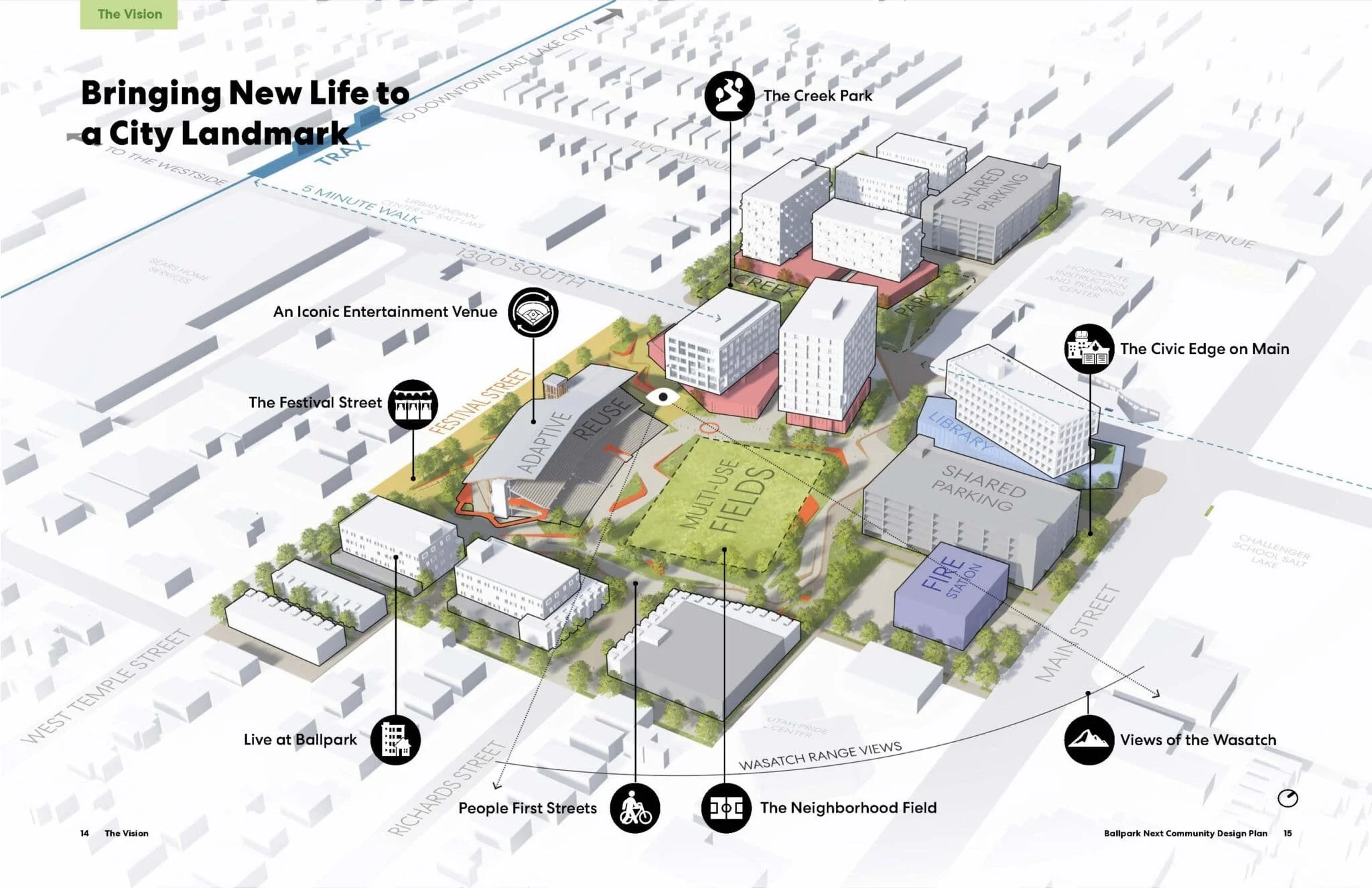

In the case of Three Creeks, it was actually portions of four natural waterways that were hidden beneath a parking lot next to an auto shop and a row of vintage homes. After the Red Butte and Emigration creeks join forces at Liberty Park, they braid underground with Parleys Creek at State Street and travel west roughly along 1300 South.

Long ago, the decision was made to bury the Jordan's major tributaries—along with all the waste and sediment collected by them—and the Three Creeks project is the first step in a larger effort to "daylight," or uncover, segments of the valley's canyon waterways.

Brian Tonetti, executive director of the Seven Canyons Trust, told me the significance of the Three Creeks project can't be overstated. It's a showcase, he said, of how buried waterways can be restored in a way that maximizes public benefit.

"It's kind of the first 200 feet in a 100-year vision to uncover 21 miles of buried creek," he said.

Price tag: $3 million.

Eventually, Murdock tells me, the city would like to add nature trails and other features to the north and south of Three Creeks. That means reclaiming city land that has been encroached on by private property owners, but he says he's not expecting much of a legal fight. I remain skeptical, as one does not simply settle a land dispute.

Along the parkway trail, an open space inside the riverbend could be used for picnic tables, a pet station or a soft walking trail parallel to the bike-friendly pavement, Murdock says. Use of the trail has surged this summer, he says, and planners are already discussing options for mitigating future conflicts between pedestrians and cyclists.

He starts to say how it's a great spot for fishing because it's a major inlet of fresh snowmelt, and it makes me think of my youth running rivers in Weber County. I think of my son growing up in Poplar Grove, and I interrupt to ask the question I know Murdock is going to hate.

"So, will it ever be a swimming hole?"

Murdock pauses. He laughs. We both laugh. I can tell he doesn't want to say, "No." I don't really want him to, either.

"I think paddling—canoeing and kayaking—I would do any day on the Jordan River," Murdock says. "I probably wouldn't be jumping in and swimming in the Jordan River right now. But I hope in the future, maybe that changes."

That he even hesitates is something of a victory. Decades of neglect, short-sighted development and jurisdictional complexity devolved the river into Salt Lake County's gutter, shuttling detritus and sewage and the occasional dead body along its path between Utah Lake and the Great Salt Lake.

But the more recent decades have trended toward rehabilitation, incrementally at times but shifting into a higher gear during the last decade, a period that coincides with the creation of the Jordan River Commission, an aquatic United Nations composed of the various public and private entities that touch the river.

And in stereotypical Knope-ian fashion, the commission is seizing on the anniversary this year to close the book on its equivalent of a master plan—the Blueprint Jordan River—and start fresh on a new vision for the next decade.

Rehabilitation takes various forms, from clearing weeds and restoring native vegetation to water quality projects like one that will open to the public in Salt Lake City later this year.

Just downriver from Three Creeks, the city's public utilities department has built a second river park next to the Day-Riverside Branch Library, complete with its own outdoor amphitheater and boardwalk. But the pièce de résistance is the manmade creek bed and waterfall that will filter stormwater pollutants and aerate the Jordan River like a fish tank bubbler.

Price tag: $2.5 million.

"Going forward, these urban water quality projects are going to have a lot more public facing, educational and recreational features," said Holly Mullen, utilities spokeswoman (and former editor of City Weekly), "so that we get more bang for the buck."

The 'Sad, Mad & Glad' Tour

Soren Simonsen, executive director of the Jordan River Commission, has been offering to take me kayaking for years now. Apparently, it took a global pandemic to make me take him up on the offer.

Simonsen reiterated that recreation along the river parkway has surged during the coronavirus pandemic. Trail counters along the river have tracked the boost in demand, and anecdotal stories abound of residents taking increased advantage of public spaces.

It's welcome visibility for the county's new and improved trails and parks, but it also places an unexpected stress test on the parkway network, highlighting the potential bottlenecks as once-ignored greenspaces become more popular.

"I think, by and large, people don't see the river as a dirty and dangerous place anymore," Simonsen said. "It still has a lot of challenges, to be sure, but the challenges are evolving."

And while the paved trail may be ready for prime time, the river is considerably less so. Simonsen and I elected to do a one-hour paddle down the Murray/Taylorsville stretch of the river, pulling out at Little Confluence Park. We did this because I'm most familiar with the Salt Lake City stretch of the parkway and because Murray was an early leader on river improvement and has an impressive corridor to show for it.

Back in 2014, Colby Frazier wrote about kayaking the Jordan River in "Invisible River" for City Weekly. I loved that article. Before that, in 2009, City Weekly writer Stephen Dark also wrote about kayaking the Jordan River in "River Rats." I've wanted to follow those up ever since.

“I think, by and large, people don’t see the river as a dirty and dangerous place anymore,” says Soren Simonsen, executive director of the Jordan River Commission.

I have a moderate level of experience in a kayak, yet I could recognize that I was inordinately nervous for how calm the trip was. The water was murky and loomed much deeper than it actually was. There was stuff everywhere in the water, mostly twigs and plants and inoffensive flotsam but ever present in an unsettling way. Every so often, my paddle would touch the riverbed, and I'd jolt from the startle.

But it was beautiful. As I pushed off from the bank and started paddling, a large black bird with a craning neck took off from a nearby rock and flew over my head. There were ducks and swallows and kingfishers, and, yes, there was litter and, yes, there were camps and graffiti. But I also kayaked under Interstate 215. That's not something I expected to do nor did I expect it to be so thrilling.

Simonsen has led this tour many times, and for individuals considerably more prominent than myself. He calls it his "Sad, Mad, Glad" tour because you feel all three on the water. He points out the storm drains under nearly every bridge that pour a generic cocktail of motor oil and effluent into the river after a rain. We pass one that is large enough to stand in, and I try to peer inside but it's pointless. I can only imagine what has poured out into the river over the years.

We also pass through nature preserves where the birdsong drowns out the city buzz. We see a family fishing together and occasionally keep up with the joggers on the parkway.

Simonsen tells me there are currently four maintained boat launches along the Jordan River. But that number is expected to swell to more than a dozen by next year, another $3 million improvement project about to break ground.

"A lot of people are discovering the great recreation benefits of paddling the river," Simonsen says. "But it's hard to access it."

After access, the next big boating obstacles are the dams and water controls. One dam, just upriver from North Temple, features a canoe chute, but many of the others are effectively impassible.

"You can't go over or under them," Simonsen said. "They are life safety risks."

Simonsen said the short-term solution is to build portages around the dams—or areas where you can exit the river and walk around an obstacle. But even that is easier said than done, he notes, and some areas could potentially host new canoe chutes built into the waterway.

But the larger issue on the water, Simonsen tells me, is that there's not enough of it, and not necessarily because of drought. The Jordan leaves Utah Lake as a wide, deep river but almost as soon as it enters Salt Lake County, it is bled dry by canals. Those segments of the parkway are great for walking and biking but are unnavigable by kayak.

"When you get past the diversion dams for all the canals at the Point of the Mountain, the river literally becomes a trickle," Simonsen said. "It's not even as big as the creeks that feed it."

And while it can be easy to write off the inconvenience to recreational users of the river, the low water levels have a more insidious effect, robbing the Jordan of its self-cleaning potential and contributing to the ecosystem damage downstream.

"Water quality has a lot to do with water quantity," Sorensen said.

But Simonsen sees room for optimism on water levels as well. He points to recent water banking legislation—sponsored by state Sen. Jani Iwamoto, D-Salt Lake City—that does not include the Jordan River but could lay groundwork for a larger program. And developers along the river are increasingly orienting their property toward the water, rather than away from it, an encouraging sign of political capital in a state where real estate is king.

"There's a lot of property owners along the Jordan River who are interested in being supportive and being partners," Simonsen said.

I ask him about the issue of homeless encampments along the river, and he gives the kind of thoughtful answer that I never know quite how to summarize. He reminds me that the Jordan River has always been a place where people go who are weary, from Indigenous and nomadic communities to the settlers who declared the Salt Lake Valley to be the right place.

"A lot of the encampments that we see are not all that different from some of the huts and shacks and sheds that were created by pioneers to weather their first couple of winters," Simonsen said.

He noted that the homeless community along the river, generally speaking, is inoffensively seeking seclusion. But he also pointed out the outsize environmental impact of illegal camps, from the waste left behind in the river to the death of vegetation that leave areas vulnerable to weeds and fire.

"Yes, there's an impact," Simonsen said. "I would say the impact is more environmental at this point than it is social."

We're Moving in the Right Direction

My last interview was over the phone with Martin Jensen, Salt Lake County's director of Parks and Recreation. He's had to deal with me geeking out over parks before and is a good sport about it.

I had been thinking about this story in poetic terms of two 10-year eras and how the decade of the bike was giving way to the decade of the kayak, and Jensen helped pop that balloon by reminding me that the Jordan River Parkway has been, at minimum, a 50-year effort and that he and his municipal counterparts are building on what came before them.

He compared it to the construction of a highway corridor—a highway for bikes? Gee, what a thought, world!—and how land is acquired, a road is built and then come the rest stops.

"The trail is in place," Jensen said. "We're making the river safer and more enjoyable every day, and now we want to put in some other things."

Traveling along the parkway trail, you can see the remnants of previous flurries of activity along the river. Weeds grow around cracked, concrete boat ramps that jut out into empty air. Yesterday's shiny new mini-parks are now rusting and claimed by squatters.

It could happen again. Maybe the virus breaks, and everyone goes back indoors. Or maybe we're all wrong, and the river is a lost cause, and nobody wants to skip rocks or watch birds or—maybe, someday—go for a swim on their lunch break. And maybe six years from now another reporter will write in City Weekly about the raw sewage floating through the west side's dilapidated green space.

Yet, Jensen said, "We're moving in the right direction. It just takes time and money and planning."

Simonsen agreed that the wind, for now, is at planners' backs. The future costs money, something in shorter supply with an infected economy, but he argued that enough pieces are in place on the parkway to encourage the feedback loop of public participation.

And right on time, the commission is currently seeking public comment on the future "blueprint" for the Jordan River. If that seems tedious, perhaps remember the Three Creeks Confluence was born out of a group of University of Utah students who started making noise about daylighting years ago.

"I feel more optimistic about the direction things are going than I did a decade ago," Simonsen said. "There's a lot of buy-in to the vision and small steps here and there inching us close to that."

Beavers So Large They Look Like Dogs

The morning after my interview with Murdock, I walked through Three Creeks to get a better look at the area. One of the neighboring homeowners was out, and I asked her what she thought about the project.

She says the construction caught her off guard, which I can tell is a nuisance but not something she wants to be publicly critical about. I asked her about crime in the area. She says items regularly go missing from her yard, and her neighbors have experienced multiple break-ins.

She also says things seem to have gotten a little worse, not better, in the past couple years. We don't talk about the city's Operation Rio Grande, but it looms in the back of my mind. The operation began on August 2017 with police from multiple agencies arresting people in the vicinity of Rio Grande Street, near the now-shuttered Road Home homeless shelter. Launched to relocate the homeless from downtown's most troubled neighborhood, it likely drove increasing numbers to river encampments.

When I ask the homeowner if I can use her name, she politely declines.

I thought about knocking on more doors, because that's something a career in journalism tells you you're supposed to do. But what do I even ask, and how do I expect a person to answer?

I live by the river. Not directly adjacent but near enough. I see illegal camps every day, as I do elsewhere in the city, and more since Operation Rio Grande started.

It's only the Jordan River where I see beavers so large they look like dogs. And I never have to worry about getting run over by a car on the parkway.

I once felt compelled to call the police when a woman come out from under a bridge and threatened me and other passers-by on the parkway trail. And another time, not long after we moved to the area, I came home from work and found a man in my tool shed.

Best I can tell, he hadn't been there long, and he was either incapacitated or hiding from my dog, barking incessantly at the shed door. He made no attempt to hurt me and—thank God—my family wasn't home.

But it was still terrifying. I called the police and, no, I don't really know what happened to him after they walked him out of my garage.

Was that the river's fault? Sure. That man would not have been in my shed without the river. Because none of us would be here without the Jordan River. That's the thing about rivers.

Did You Know?

You can help update the new "blueprint" master plan by adding your comments to the public survey at: BlueprintJordanRiver.org.

The Folsom Trail will be a paved walking and biking path connecting the Jordan River Parkway Trail to downtown Salt Lake City. The first phase of construction is anticipated to begin in fall 2020. It will follow a former rail corridor from 500 West at North Temple to the Jordan River Bridge and Fisher Mansion near 200 South

Tracy Aviary is in the process of adding a second campus at the Jordan River. Called the Tracy Aviary Jordan River Nature Center, it will offer education and conservation programs with the goal of connecting people to nature and helping preserve the naturalhabitat. Transitional building units opened in the spring of 2019, with construction for a new facility slated to begin in 2020. 1125 W. 3300 South, South Salt Lake

The Salt Lake City Boat Access Improvement project has constructed two new boat access locations along the Jordan River at Fisher Mansion (1206 W. 200 South), and at the Redwood Trailhead (1850 North Redwood Road).