Then and Now: Kids Organized to Protect the Environment

Authored by Lynne Olson

Source: Catalyst Magazine

Hidden Hollow, in Salt Lake City, was protected through the dedication of school children and their group “Kids Organized to Protect the Environment.” This is their story.

In 1990, a group of SLC elementary school students in search of a problem-solving project saved an abandoned gully from being paved over and transformed it into a nature preserve. Their successors began a project that resulted in the Draw at Sugar House. We revisited the KOPE kids’ victories, and checked in with some of those students today.

Salt Lake City first heard of the Kids Organized to Protect our Environment, the KOPE Kids, in 1989. Environmental activists were planning for the 20th anniversary of Earth Day, and students at Jackson Elementary in SLC made headlines by initiating the cleanup of a hazardous waste site near their school.

Inspired by the Jackson kids, students at Hawthorne Elementary agreed to meet every Friday during the summer break to tend their school’s new native plant-and-herb garden. While they worked, they considered other ways they could help their neighborhood. The children named their group, Kids Organized to Protect our Environment,” or “KOPE.” The KOPE Kids began their problem-solving career by demonstrating the need for a recycling center in Sugar House. A year later, the 4th, 5th, and 6th graders found an empty lot behind a busy shopping mall, and launched their signature project to create Hidden Hollow Nature Preserve.

Cassie Olson is one of the original group of kids that started the KOPE Club, and one of the group that fell in love with the abandoned field and named it Hidden Hollow.

“We were learning about problem-solving and the brainstorming process. We wanted to encourage everyone to plant gardens using native plants. When we found that beautiful stream with its open land that had been left to go wild, it was wonderful. We imagined we’d found something that no one had ever seen before.” As they learned in doing their research, however, it was once the site of the first Sugar House Park.

Hawthorne’s Extended Learning Program (ELP) teacher, Sheri Sohm, remembered the children asking if cleaning up the stream could become their next problem-solving project. “This area of Sugar House had been the dumping site for construction debris for over 50 years,” says Sohm. “The stream was down in a gully like a mountain stream. The north bank still looks much like it did then, with vegetation growing over construction debris.”

The next year, students learned that developers intended to cover the stream and build big box stores, office buildings and a parking lot over the block.

However, they were convinced the stream could be rehabilitated and would be an asset to the businesses.

Teacher and students brainstormed the problems they might encounter. “The first was building public awareness and community support,” says Sohm. “It looked so bad, and needed so much work that it was difficult for anyone to imagine the potential we saw. The second problem was money. The land was valuable as taxable property. Trails and parks need upkeep and drain public coffers. Commercial development brings in tax base. We had no money and didn’t know anyone with any.”

The students identified other values for the open space; it also had educational, aesthetic, recreational, historical and environmental value. These became the topics for extended research during the following years.

“We integrated the different subject areas and the political process into ELP curriculum,” says Sohm. “Students learned how to speak in front of groups. They researched the human history and studied biological ecosystems.”

“We went back to the Hollow with biologists, geologists and scientists who helped us discover which plants and animals belonged there,” recalls Cassie. “I was astonished to discover how much wildlife was surviving in the middle of our neighborhood.”

“We collaborated with people from other schools; government officials; the business community; journalists; donors who saved us at various times; and parents who made time to coach their kids and drive them to meetings,” says Sohm. “It’s hard to describe all the wonderful things that came together to preserve Hidden Hollow.”

In 1991, the KOPE Kids were invited to Washington, DC to accept the President’s Environmental Youth Award for their accomplishments. At the Awards ceremony, Pres. George H. W. Bush said, “Together they transformed that unsightly trash heap into a nature park, and they gave it a new name, Hidden Hollow. And today, it’s a learning center for other students, a kind of outdoor classroom. And what you’ve done tells other kids that you can make a difference.”

Big Ideas

Although developers had planned for a shopping center to cover the stream, the KOPE Kids wanted the City to rezone the property as a park. When asked to comment on that idea, the developers said the students would never receive enough support or money to accomplish their goals. The kids took that as a challenge, and with encouragement from their teachers and parents, the students focused their efforts on marketing and fundraising.

The KOPE Kids became proficient at public relations. Beacon Heights’ 4th, 5th and 6th graders issued a Hidden Hollow media advisory in 1997: “We have a special interest in a natural open space in Sugar House called Hidden Hollow. We have been promoting the restoration and preservation of this area. We want to increase awareness of this area so others will come and enjoy it. We are taking other schools on tours and working with city officials, the Sugar House Park Authority, Sugar House Community Council, UDOT and even the Governor to get a tunnel under 1300 East so people can safely cross from Sugar House Park into Hidden Hollow. We are working on ways others can learn more about the water, soil, plants, birds and insects in Hidden Hollow. We are creating a web site with a virtual reality field trip, a guide booklet explaining life-cycles, and site markers to help people understand what to look for as they walk around the area.”

KOPE Kids also learned how to apply for grants. They received a city Self-Help grant for an iron gate to stop illegal dumping in Hidden Hollow. Initial funding for restoration of the nature park came from Community Development Block Grants. Insofar as Hidden Hollow was located within the Redevelopment Agency’s Sugar House Project Area, the Agency budgeted the necessary funds to plan and complete improvements for the park. Many more thousands of dollars came from cash and in-kind donations, including a gift from Stephen C. Richards of nearby Granite Furniture Co. He wrote, “I want the KOPE Kids to use this to purchase some good sturdy benches to put along the creek. Putting them there will give tired old men like me a place to sit and rest.”

On September 1999, almost 10 years later, the city marked the official opening of the Hidden Hollow Natural Area with a celebration at which business owners, students, politicians, developers and neighbors pressed their hands into the new cement pathway, acknowledging all those who had made the project a reality. In 2000, Salt Lake City permanently protected Hidden Hollow Preserve through a conservation easement to Utah Open Lands Conservation Association.

In the decade that followed, the KOPE Club expanded to Beacon Heights, M. Lynn Bennion, Lincoln, Parkview, and Oakridge elementary schools. The KOPE Club at Oakridge re-landscaped the schoolyard in a project they called “Naturescaping,” landscaping with native plants to sustain wildlife in the city. At South Kearns Elementary, the “SKOPE Kids” developed a program to protect burrowing owl habitat in a rapidly growing area of Salt Lake County.

Each club was directed by a committed teacher who taught language arts, math and science skills, art and even music through beyond-the-classroom experiences in the real world.

“The children realized they could use the problem-solving skills they learned in the classroom to identify problems in their community,” said Penny Archibald-Stone, an ELP teacher at M. Lynn Bennion School. “One problem they [the Hawthorne students] found was that kids don’t get enough good publicity. They decided to publish a newsletter to let people know the great things kids are doing around Salt Lake.”

The Hawthorne Club started writing articles and gathering information from other schools about what they were doing. They designed a logo and named their newsletter “The KOPE Kronical.” During the 1991-92 school year, the Club published nine issues and sent them to schools throughout the Salt Lake City school district.

In 1993, 6th graders at Bennion formed their own branch of KOPE and took over the “Kronical.” The paper was funded by donations and a Self-Help grant from the city. By 1998, it had a circulation of 20,000, delivered to every school in the district. The editorial staff hosted annual workshops for student writers and editors, with professional journalists as mentors and advisors.

In addition to the “Kronical” conferences, KOPE clubs organized annual Earth Day celebrations and four Children’s Conferences on Sustainability, which provided a forum for student research on endangered species, air and water pollution, and local environmental issues such as feral cats in urban neighborhoods.

In 1995 and 1996, more than 600 students from public and private schools joined the KOPE Kids in a March for Parks along the Parley’s Trail Corridor to Fairmont Park. They raised funds to benefit Hidden Hollow and for the City’s new “Urban Tree House” Environmental Education Center.

In 2000, a year after KOPE Kids celebrated the dedication of Hidden Hollow, Parkview Elementary students helped design a two-acre open space on the Jordan River called Bend-in-the-River. In a story for the “Kronical,” they wrote about working with the University of Utah Bennion Center and TreeUtah to make the Urban Tree House at the Bend a place “to observe plants and animals, study habitat, learn about predator/prey relationships, and to do art projects.”

Parley's Trail and the Draw at Sugar House

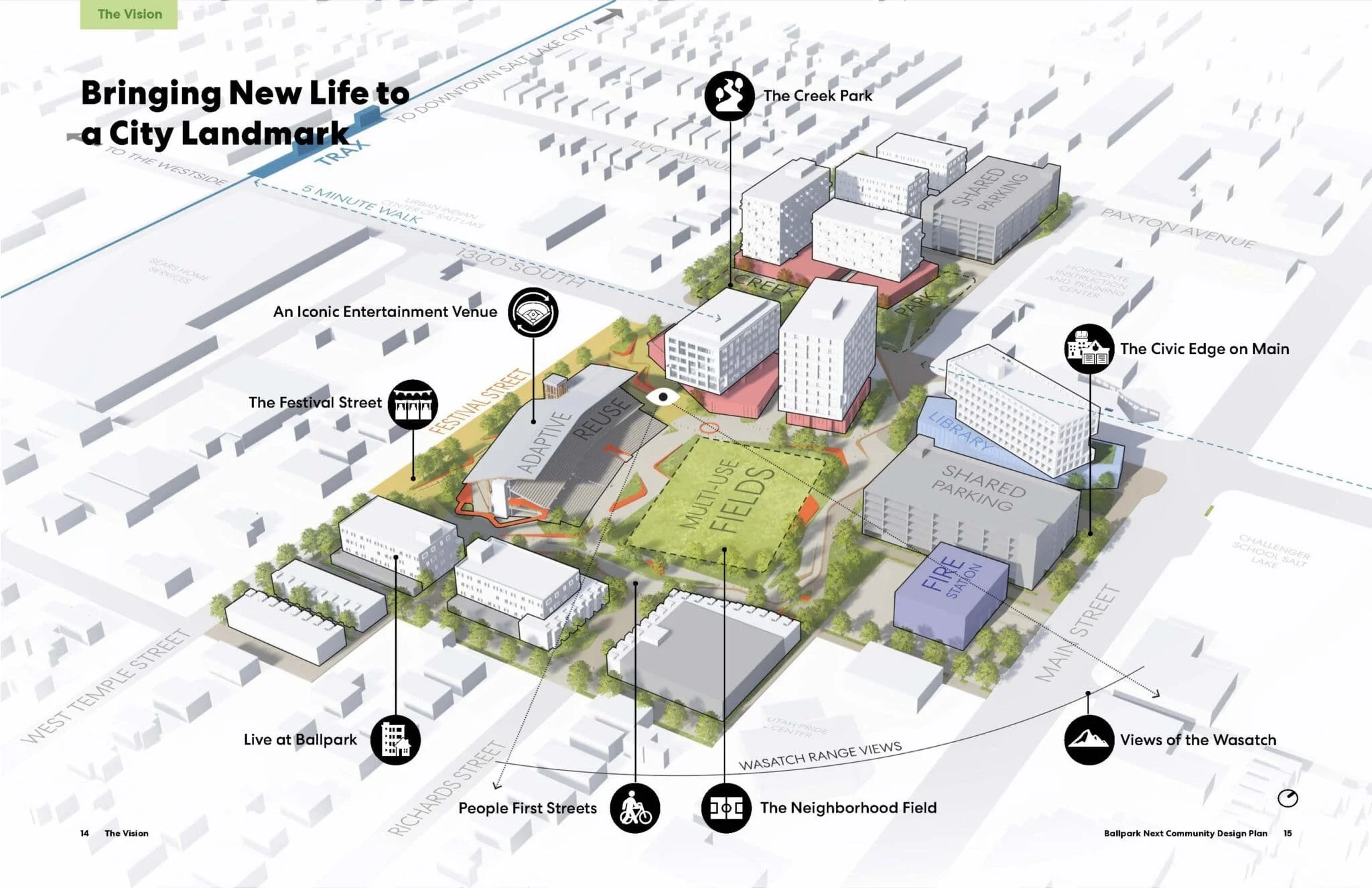

In 1992, Salt Lake City planners had proposed development of a network of parks, greenways and bicycle/pedestrian trails. A map of the Parley’s Creek Corridor showed a trail connection from the mouth of Parley’s Canyon to Hidden Hollow, and mentioned the KOPE Kids as potential Corridor Keepers. Eleven-year old Alex Phillips and other KOPE members presented a case for adopting the Salt Lake City Open Space Master Plan at a public forum at the Utah Museum of Natural History.

Beginning in winter of 1999, Beacon Heights KOPE students met with government officials and community leaders to collect information for a project to connect Sugar House Park and Hidden Hollow with a trail crossing at 1300 East St. With their ELP teacher, Coleen Menlove, they identified resource specialists who understood the difficulty of crossing the busy street. They contacted individuals with a special interest in a pedestrian and bicycle connections along the Parley’s Creek corridor, and requested letters of endorsement from groups that supported their efforts. After months of meetings with community representatives, the KOPE Kids resolved that the safest way to cross the street was to dig a tunnel under it.

Sugar House Park Authority President Clark Nielsen wrote a letter of support for the KOPE proposal, saying the plan offered access to the Park from the commercial business district and reconnected the Park to the greater Sugar House area. During a press conference at the State Capitol, Beacon Heights “Kronical” reporters Nikola Hlady and Griffin Bullock asked Governor Michael Leavitt for help with their trails project, and he offered them advice on how to gain public support and funding for the pedestrian crossing under 1300 East St.

When Salt Lake County completed a Master Plan for Parley’s Creek Corridor Trail, it included recommendations for the 13th East Crossing that incorporated many of the KOPE Kids’ ideas. The government officials and resource specialists who had advised the Beacon Heights students organized themselves into an advocacy group called the Parley’s Rails, Trails and Tunnels (PRATT) Coalition.

In 2003, Salt Lake City’s Planning Director Stephen Goldsmith received a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts to solicit designs for the 13th East Crossing. The winning design was named “the Draw at Sugar House.” Environmental artist Patricia Johanson was lead designer for The Draw. Mayor Rocky Anderson honored the design team at a press conference in Hidden Hollow. Alumni of the Beacon Heights’ KOPE Club and their teacher Coleen Menlove were there to celebrate their achievement.

This summer, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City, and the PRATT Coalition will announce the completion of the Sego Lily Dam at the Draw in Sugar House Park. In recent years, the KOPE Kids from Hawthorne School found a variety of ways to contribute to that effort. 5th and 6th graders polished their public-speaking skills to persuade decision-makers to finish the Sego Lily Dam, while 4th graders built a three-dimensional model to help the prospective sponsors grasp the scale of the construction. Patricia Johanson visited the students in their classroom to explain the historic narrative that inspired the monumental artwork.

In 2016, for the final project in their nearly 30-year career of community problem solving, the gifted KOPE Kids received public recognition from the National Parks Service. Their work is captured in a NPS YouTube video, “Where have all the Sego Lilies Gone?”

In 1995, Julie Malinsky, 12, addressed then-Mayor Deedee Corradini and City Council about the significance of Hidden Hollow. “Ever since I joined KOPE, we have been learning how important it is for young people to feel connected to the place where they live,” she said. “When we study its history and traditions, we also learn to put a high value on our community. That gives us the skill and the power to protect our neighborhoods, and to protect and improve the quality of life we have here.”

Alex Phillips (now 38, and a certified arborist and landscape designer/ planner) says, “I never realized how those lessons shaped who I am and how I think. I often find that when colleagues come upon a challenging situation, many either don’t proceed without guidance or they reach a conclusion that must be corrected down the line. They don’t think critically about it, organize their questions, answer what they can, and then research the rest. It never occurred to me that maybe they were not given the opportunity in school to learn those skills.”

Nikola Hlady studied Green Urbanism at Pomona College, received an Emerald Necklace Fellowship from Amigos De Los Rios, and a Masters Degree in Urban Planning from USC. He currently works as assistant planner for the City of Claremont, CA.

Griffin Bullock is currently a resident in internal medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center planning on completing training in cardiology. He graduated from the University of Utah in Chemistry and from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Katrina Smithee, BSN, RN, CNOR, spent five years as a nursing assistant before graduating in 2013 from the U of U with a BSN and an honors degree in theatre studies. She has been working ever since as a PeriOperative Nurse in the Clinical Neurosciences Center of the University of Utah. Katrina, who is now 30, credits Mrs. Menlove and others in the Extended Learning and MESA programs for encouraging her achievements. “I live in Sugar House so walk through Hidden Hollow and into Sugar House Park on a regular basis, to picnic or feed the ducks and geese or walk my friends’ dogs. It’s a peaceful little oasis that I am personally grateful for and so happy to have been a part of.”

Lindsay Ploeger now works as a Physical Therapist Assistant in multiple skilled nursing facilities around the valley. She has a 19-month old daughter who loves the outdoors and especially walking around Sugar House Park and looking at all the sites.

Cassie Olson is associate principal cellist at Ballet West, and Cello Faculty at Waterford School. In an interview for Utah Open Lands’ podcast series, “Acres Away,” she said her experiences with the ELP and KOPE programs were very influential. “They gave me a tangible sense of how a person’s actions could influence a whole community. Even as children, we could see a direct connection between choices we made and their consequences for the environment. That is why I try to be eco-conscious in my daily life, and why I feel strongly about current political and environmental issues.

“The ability to solve problems is a skill that I use every day in my life as a teacher and performer,” she says. “With my students, I need to find individualized ways to help them achieve success. Being able to analyze a problem that I see and come up with creative solutions allows me to engage and empower my students.”