Realigning a downtown rail line could turn a neighborhood into a no-horn haven

Authored by Heather May

Source: Salt Lake Tribune

An article detailing the impact of the Folsom rail line realignment in Salt Lake City, UT. It details the restoration of City Creek for habitat value and as an urban fishery, and highlights the Folsom Trail as a regional connection.

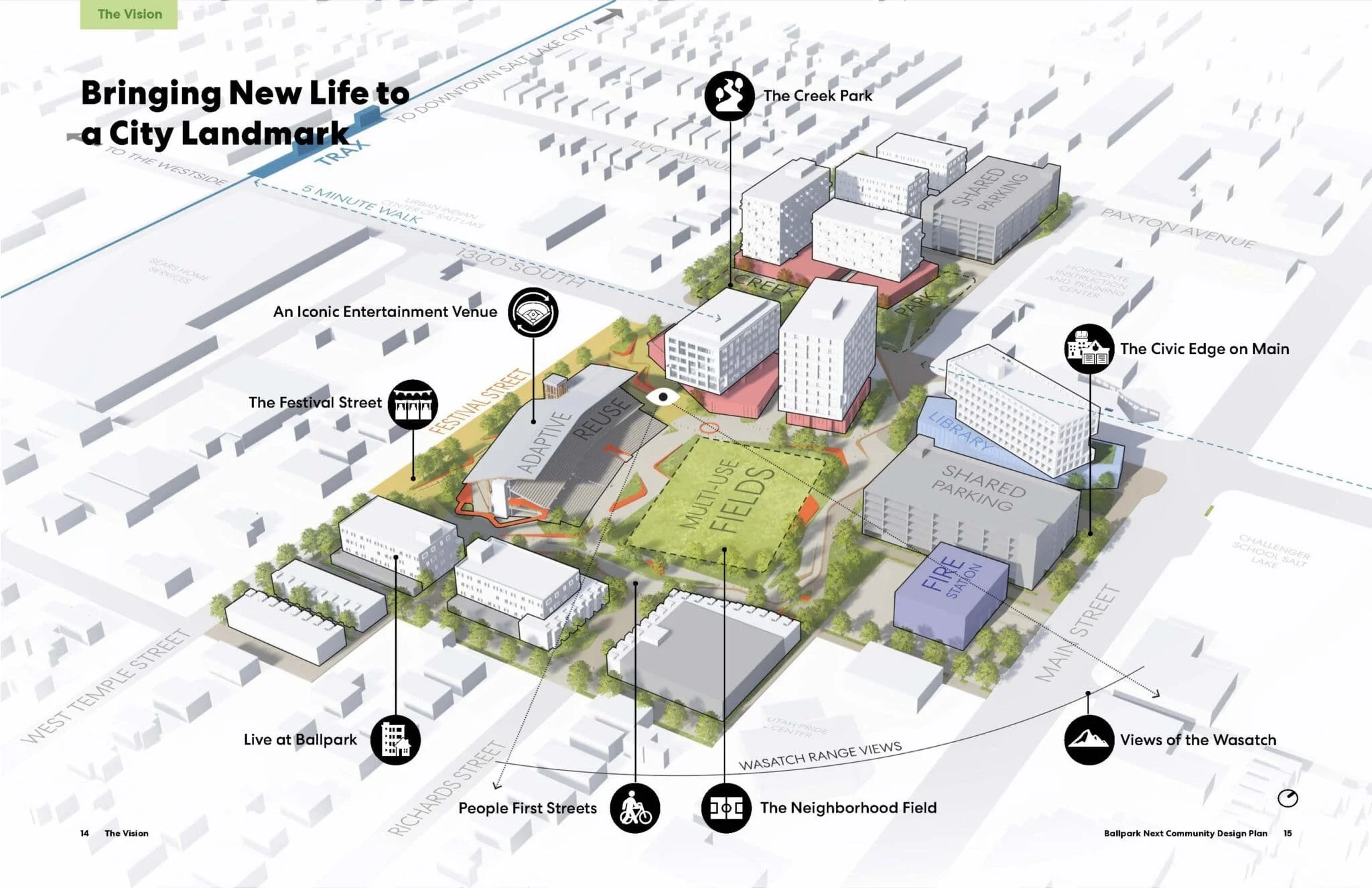

City Creek - the waterway that sustained Mormon pioneers but later was partially buried by their descendants - could rise again, gushing from The Gateway to the Jordan River Parkway and sweeping up a neglected neighborhood with a spurt of new development.

The creek - along with a bike and pedestrian path that would link to the Jordan River trail - is on the drawing board, thanks to major changes planned for railroad tracks downtown.

The city, Salt Lake County and Union Pacific plan a $50 million project to realign a tangle of railroad tracks, known as Grant Tower, west of The Gateway. The primary motive for the project is to remove noisy trains that roll along the 900 South rail line through west-side neighborhoods.

But, as an offshoot of that arrangement, UP's rail line on Folsom Avenue (45 South) could turn into a river. UP expects to abandon about 1 1/2 miles of its Folsom track between 700 West and the Jordan River, and the city hopes to funnel some of City Creek from its tomb under North Temple.

"It will be an enormous benefit to the city," predicts D.J. Baxter, senior adviser to Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson. "It seems every eight to 10 years we have an opportunity like this that comes along to allow us to undertake something so substantial that it will really affect the future of the city."

By his count, the last time was in the late 1990s, when the city, UP and the Utah Department of Transportation consolidated railroad tracks downtown and shortened freeway viaducts, opening 650 acres for redevelopment and giving birth to Gateway.

The city hopes freeing City Creek will spur more housing near downtown. Baxter also views the river as a way to bridge the psychological barrier between east and west created by the physical barriers of Interstate 15 and the railroad tracks.

"More than anything we've done in recent memory, this will reunite the east and west sides of the city," Baxter says.

That is, if the project is built. UP and the city have yet to finalize the Grant Tower deal. And then there's the matter of money for the city's river of dreams.

Critical Creek

From the beginning, City Creek was vital to Salt Lake City's development.

The advance Mormon pioneer party used its water to soften the soil so that, when Brigham Young arrived, five acres of potatoes already had been planted. The river provided drinking and irrigation water, and it powered a sawmill, flour mill and silk plant, according to research by Ron Love, a city public-services planner.

In the early 1900s, crews buried the creek's original branch, which paralleled North Temple, to protect the water from contamination and the public from drownings. The portion running from City Creek Canyon down to Memory Grove was left alone and remains a popular recreation spot.

"It probably was a nuisance and a health hazard," says Love of the North Temple tributary. He notes old photos of City Creek show a boggy, muddy place, a breeding ground for mosquitoes.

Even so, folks have yearned for decades for the river's return. In 1995, the city brought water to the surface at City Creek Park, on the corner of State Street and Second Avenue. The LDS Church's Conference Center includes a stream, and the Olympic fountain at The Gateway is another attempt to represent the creek.

The new creek would not snake along its historical path. A feasibility study has shown the Folsom alignment will work despite the water running next to formerly contaminated sites - including a defunct barrel-storage site and a coal-gasification operation.

Love stresses the sites have been remediated. Flooding shouldn't be a problem either because the city expects to maintain a culvert under North Temple to divert any threatening runoff.

But funding? That's another matter. Federal dollars have dried up to even finish the feasibility study. The cost of restoring the creek is estimated at roughly $5 million. Construction could start in 2008, once Grant Tower is complete.

The aim is not a San Antonio-style Riverwalk, a tourist destination with hotels, restaurants and clubs. While Salt Lake City has contingency plans for a park on Folsom, the goal for now is a natural habitat surrounding the creek, which could become an urban fishery, much like the Jordan River.

Love says the trail could connect to a regional system and take a biker or runner from downtown Salt Lake City to Provo or Evanston, Wyo.

Nevertheless, the city hopes urban development will flow with City Creek. The river - along with the proposed light-rail spur to the Salt Lake City International Airport and the planned commuter rail from Weber County to downtown - is the impetus behind a proposed master plan for the Euclid neighborhood (between North Temple and Interstate 80 from I-15 to the Jordan River).

"If we put a green area through here with a meandering stream, I can't imagine how that would not contribute to the redevelopment of this area," says Love, standing on a dirt road west of The Gateway near tumbleweeds and a wire fence that demands "No Trespassing."

"Urban creeks are just wonderful areas. Consider that sort of thing as opposed to the railroad. Which would attract you?"

West-side Story

Euclid originally was a residential enclave, but zoning changes in the 1960s brought industrial and commercial uses.

Then I-80 and the railroad tracks came, exiling the neighborhood. Today, pockets of homes sit next to manufacturers. The housing stock is suffering, with well-kept homes next to uninhabitable ones.

Residents say drug deals and prostitution used to be common. "At first we had, you name it, drug dealers, alcoholics, crack whores," says Perry "P" Brown, manager of the Utah International Hostel, on 800 West and Folsom.

But residents like the area because it's close to the freeways and downtown. The people are diverse and the mortgages low.

Outsiders see it as "the slums," says Mary Stephenson, who has worked at Trophies Inc., 831 W. 100 South, for 40 years. "It's a good neighborhood."

"I don't care about the hookers. They don't bother me," says Virgil Topp, who has lived in the area for 13 years, managing duplexes on 600 West near South Temple. "I like it just the way it is. It's like country to me. It's in town but it's back from town."

There are plans to turn the area into an extension of downtown. More high-density housing is mapped out on 500 West and 600 West. The draft master plan calls for housing overlooking the creek, along with neighborhood retail.

Mark Leese wrote the draft master plan for Euclid as director of urban design for Denver-based URS Corp. He says the city will need to rezone some properties and redevelop them to take advantage of the creek.

"If the city stops right there [surfacing the creek] and doesn't go any further, there won't be much to it," he says. "There's a terrific opportunity for redevelopment to occur on both sides of that creek. It would just turn this into the place to be."

Businesses already exist on Folsom and some neighbors bristle at the possibility of being shoved out.

At the circuit-board manufacturer Schovaers Electronics, Judy Green says the idea of a creek running through an industrial neighborhood is odd.

"It's not that great a part of town," she says. "It almost seems like they're trying to appease the west side."

But her brother, Bob Schovaers, says he would like to see the creek running next to the family business at 22 S. Jeremy St.

"It seems like everything they're doing is east of the freeway," he says. "It'd be nice to see something happen west."