Crude Awakening

Authored by Colby Frazier

Source: City Weekly

An article describing the long-term impacts of the 2010 Chevron oil spill to Red Butte Creek and the residents that live along its banks. Volatile organic compounds, associated with the oil spill, may be leading to health complications and the death of at least one resident, Peter Hayes.

The death of Peter Hayes has dredged up fears that Red Butte Creek's 2010 oil spill not only harmed the waterway but also the health of those who live along its banks.

In winter, the water of Red Butte Creek drifts at a slow and steady rate through what was Peter Hayes' backyard. The creek, as it flows beneath 900 South, appears inky against the white snow heaped on its banks.

To Peter Hayes, his house became its own entity, and the creek there—modest in size and surrounded by homes—was nevertheless a creek, a moving, live body of water that carried itself toward some unknown union with other, perhaps greater, stretches of water.

"It had to do with the place itself, the creek being an integral part of that," says Heidi Hayes, Peter's sister. "And being by the water there was really important to Peter."

They say Peter was one of the most capable river guides to ever wrap his thick fingers around an oar. And after more than two decades as a river bum, guiding approximately 75 trips down Class IV whitewater on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River in Idaho, he took a step back from full-time river-running, and settled down in Salt Lake City, where he started a family and taught ninth grade biology at Rowland Hall.

The average trip length on the Middle Fork is six days, meaning by the time Hayes hit his mid 20s, he'd spent just over a year floating on that river alone.

Even when one leaves the river for new strands of adventure, the roar of rapids and the freedom granted in fortunes on a wild river cannot easily be expelled from the brain.

And so it was that Peter Hayes got a house by a creek that moved and murmured and ebbed and spoke in the same way as all the rivers of the world.

"The river—and it's kind of a funny thing—the river isn't one river, it's just the river, and wherever you are around a creek, a stream, a river, there's a feeling of home there and of belonging and it's a very unique environment," Heidi Hayes says. "An incredibly important part of that home was that creek, and that place to him was exceptional."

On Sept. 15, 2015, 60-year-old Peter Hayes suffocated. A couple of years before his death, Hayes began to cough. His sister says he thought he was coming down with asthma. But a trip to the doctor ruled this out, and eventually, Hayes learned his lungs were slowly but surely eating themselves up.

That's what idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) does—it suffocates its victims by destroying the tissues that distribute oxygen into the bloodstream. According to the Coalition for Pulmonary Fibrosis, a nonprofit that aims to generate research and find a cure for the disease, 48,000 new cases of IPF are diagnosed in the United States each year. The disease has no definitive cause and is incurable. Hayes received his death sentence in January 2013, roughly three years after an event that would change the course of his final years. Just before 10 p.m. on June 11, 2010, a pipeline ruptured and 800 barrels of toxic crude oil rushed down Red Butte Creek, spewing high levels of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) into the air and into the homes of those who slept with their windows open during a balmy summer night.

The usual scene unfurled: Emergency crews arrived, politicians and public-relations experts spoke to cameras and, after months and years of cleanup, the creek has begun to resemble its old self. And through it all, the creek, the soil, the birds and the creekside residents had an unofficial spokesman: Peter Hayes. Like the politicians, he stood before the cameras—his gray mustache curled up like a Wild West gunslinger—demanding that someone take responsibility for the spill.

Peter—his neighbors, friends and colleagues say—demanded that the creek be restored to health and that residents who huffed the fumes as oil burst into the creek for hours before being detected, be taken care of.

While the pipeline operator—Chevron Pipe Line Co.—spent north of $40 million, according to media reports (Chevron declined to provide an exact number), to clean up the spill, it forked over only $4.5 million in penalties to local and state entities, much of which was spent on water-quality and restoration projects.

The kind of health support Peter sought never came close to being realized. While a Chevron Pipe Line Co. representative did respond to City Weekly's questions about the spill, he declined to answer any questions about health impacts or studies. The only monitoring of human health arising from the spill is a pledge by Salt Lake County and the state health department to conduct a cancer-incidence review of the zip codes surrounding the creek every five years.

But Peter, a rock of healthy living, suffocated—a fact that has left many of his neighbors ill at ease as they wrestle with the possibility that his death could have been caused by exposure to crude oil—the same oil that hundreds of residents were exposed to.

In his final days, Peter's mouth became so dry that his family would spray his tongue with water so it could become unstuck without tearing away the skin tissue.

In Peter's mind—his friends and family say—was an unshakable belief in what had caused his lungs to abandon him: That river of crude oil, the VOCs that filled his home that morning and for weeks afterward, and that 63-year-old steel pipeline just up the road from his house which tirelessly delivered 15,000 barrels of crude every day to Chevron's oil refinery.

"I did not have him ever tell me that it could be something else," Heidi says. "He felt like it was the creek."

Anatomy of a Crude Oil Pipeline

Originating in Rangely, Colo., Chevron Pipe Line Co.'s crude-oil-pipeline system dips and dives over a 182.5-mile stretch of rugged Western land. As it gathers crude from Rangely and three other areas, it crosses the Green and White rivers in the Uintah Basin, and then glides across much of Utah's watershed, grazing the upper Provo River near Woodland, crossing Parley's Creek, Red Butte Creek and then Emigration Creek before depositing its product at Chevron's refinery in Salt Lake City, where it is turned into gasoline and other petroleum products.

From Wolf Creek Pass along Highway 35 near Hanna, Utah, to its final destination at the refinery, the pipeline loses 4,216 feet in elevation.

Jeff Niermeyer is the former director of Salt Lake City's Department of Public Utilities. With a vast understanding of the city's drainage system, Niermeyer's voice was crucial in the early days, as well as the aftermath, of the spill. He says that for 20 of his 25 years in the public utilities department, he didn't think too much about the hazardous materials carried by pipelines that crisscross the valley.

But since the Red Butte Creek spill, he says that, on some days, his mind is as focused on oil as it is on water. "It really opened my eyes to the extent of these energy pipelines going through our community," Niermeyer says. "It's something we can't live without, but how do we live with them?"

In news stories about the spill, the official cause was often identified as an "electrical surge," or an "electrical arc."

Though the pipeline is getting on years, Niermeyer says its age had nothing to do with the rupture: The cause, according to Niermeyer and incident reports prepared by the federal Pipelines & Hazardous Materials Safety Administration [PHMSA], was a failure by Chevron Pipe Line Co. to maintain its right of way.

The electrical surge blamed for the June spill transpired through a series of events dating back to the 1980s, when Rocky Mountain Power built an electrical substation near the pipeline. Later, the power company installed a fence around the substation. One fence post was pounded into the earth directly above the pipeline.

Some 25 years later, on June 11, 2010, a typical high-mountain thunderstorm flashed through the Salt Lake Valley, ripping branches from trees and setting off flashbulbs of light in the night sky.

An exact cause for the electrical surge has never been identified. But Niermeyer, as well as federal incident reports, indicate that a branch likely dropped onto power lines near the electrical substation. The branch then came in contact with the substation fence, electrifying it. And since electricity is always in search of a ground, it jolted through the fence post above the pipeline, traveling through the ground, jumping into the pipe and ripping a hole the size of a dime in the steel. The electricity then exited at the south side of the creek at a valve station.

PHMSA's incident report notes that Chevron knew about the fence post, and even installed a pipeline marker near the post that caused the leak. "There is no record that Chevron ever identified this transition station as something that could be detrimental to their pipelines," the report states. "Chevron had installed a pipeline marker within one foot of the metal corner fence post that was installed over their No. 2 pipeline."

At the time, Chevron Pipe Line's spill-detection technology consisted of monitoring how much oil was put into the pipe on one end, and doing the same on the other end, PHMSA reports show. If a discrepancy occurred, it could be due to a leak. But rather than the company immediately shutting down the pipeline, Niermeyer says, the custom at the time was to send employees into the field to check the pipeline, much of which runs underground.

In the early morning hours of June 12, emergency responders estimated that 50 to 60 gallons of crude oil gushed into the creek each minute. A corrective action order from PHMSA says that Chevron did not detect or respond to the pipeline failure for more than 10 hours. The first emergency responders were members of the Salt Lake City Fire Department, who first saw oil in the creek just before 7 a.m. after receiving a complaint about petroleum odors at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center on Foothill Drive.

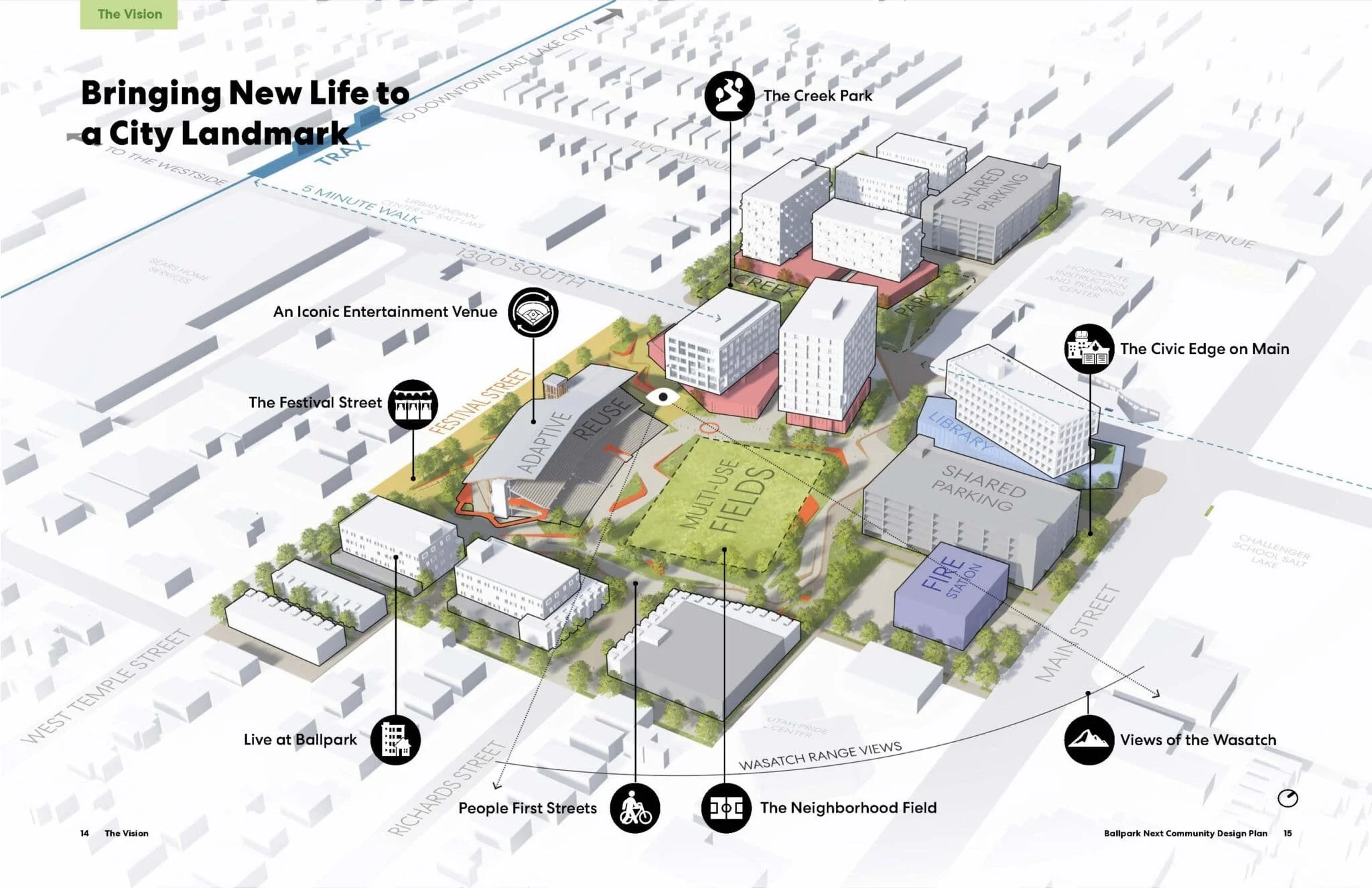

A short time later, Niermeyer himself was on the scene. The creek, he says, flows through an open channel from the mouth of Red Butte Canyon to roughly 900 East, where it sinks underground into a series of concrete culverts. It travels south on 700 East, and then cuts west at 1300 South, where the majority of the water flows downhill until reaching the Jordan River.

Shortly after firefighters reported the spill, Niermeyer says his storm-water crews had already detected some oil entering the Jordan River. The oil was threatening sensitive wetland areas not too far downstream.

He says a decision was made to cut off the flow headed down 1300 South and divert the entirety of Red Butte Creek into Liberty Lake at Liberty Park.

"I knew that if we did that diversion, we could capture most of that oil in Liberty Lake before it made it further down the system," Niermeyer says.

A bigger challenge, he says, was for Chevron to shut down its pipeline, a difficult task that Niermeyer estimates took around 10 more hours. Because the pipeline travels so far and over so much varied terrain, Niermeyer says that simply shutting down an emergency valve could have caused a spike in pressure somewhere along the line, and with potentially tons of crude bearing down, might have split the pipe, resulting in another oil spill.

"That's one of the sequences that took a long time back in June of 2010," Niermeyer says. "They were shutting that valve down slowly, draining the pipe, so that you didn't exceed the capacity of that line, creating a much bigger problem."

By the time the pipeline was shut down in the afternoon of June 12, an estimated 800 barrels, or 33,600 gallons of crude had fowled Red Butte Creek, exposing 190 residences and a number of businesses to its fumes.

By volume, 800 barrels is small potatoes. In 2013 and 2014, Kennecott reported a pair of spills of polluted water totaling 514,000 gallons, according to spill reports filed with the Utah Department of Environmental Quality.

And spills of crude oil regularly occur in the Uintah Basin, but Niermeyer says no one is around to be hurt by them.

But the Red Butte Creek spill, says Walt Baker, director of the Utah Division of Water Quality, while not spectacular in size, was monumental when viewed through the lens of those impacted.

"As far as the threat and the impact, I think there've been larger spills, but none of the consequence of Red Butte," Baker says. He went on to say it's a "fair characterization" to call the Red Butte spill the most serious in Utah history. "It's uncommon to have an oil spill like that in an urban setting," Baker says. "Almost unprecedented, nationally."

The Smell of Oil in the Morning

Annie Payne lives south of Miller Park, a 9-acre patch of open space owned by Salt Lake City. Red Butte Creek cuts through its center, creating an oasis of river, trees and trail in the middle of a neighborhood. Payne awoke on June 12, 2010, at 6 a.m. to what she remembers as "an overwhelming smell of oil."

Payne walked to her children's room where she found her 4-year-old daughter and 5-year-old son sound asleep. "Both of them had wet the bed, and they were sleeping in their own urine, and I couldn't wake them," Payne says. "For a few seconds, I thought they were dead."

Payne and her family spent the next couple of days in a hotel, then left town for a couple of weeks for a family reunion. When Payne returned, her friend and neighbor, Peter Hayes, reached out to her. "He was busy organizing," she says.

While Payne quickly realized that she and her family had been exposed to something with potential health hazards, one fact stood out: There was no coordinated evacuation nor notification in the immediate hours after the spill alerting residents that anything was wrong.

The only person who banged on Payne's door was a representative—of which organization she does not recall—who told her, "It's safe to stay in your house, and we will not pay for you to stay in a hotel."

For Joe Cook, who, like Payne, owns a home that borders Miller Park, the day of the oil spill was life-changing. He says his home, the creek and his health were one way before the spill. But now, they're all different.

Cook recalls smelling an "organic odor," but he didn't immediately seek out the source, nor did he flee. "It's not as much of an insult that would cause you to pack up and go to a hotel," Cook says of the smell. "But there are probably many toxic substances that don't assault the senses and directly repulse someone to the point where they seek relief."

Cook says he and his daughter both felt ill the evening after the spill, but he toughed it out. Since then, though, Cook says he's been diagnosed with cardiopulmonary issues, meaning that he has a hard time breathing because his blood isn't receiving adequate amounts of oxygen.

Cook's daughter, who is in her 30s, also has pulmonary issues and now uses an inhaler. Both Cook, Payne and other neighbors say that at least two area women have been diagnosed with breast cancer, and that a woman living across the creek from Peter Hayes died of lung cancer.

Roughly 60 property owners affected by the spill were part of a lawsuit, Peter Hayes v. Chevron Pipe Line Co., filed in federal court by Paul Durham, a Salt Lake City attorney, seeking compensation for property damages. In a Salt Lake Tribune story published March 25, 2012, Durham was quoted as saying the lawsuit sought "tens of millions" in compensation. The case was settled in 2014, and the details are confidential. Durham did say that Peter Hayes was the "moving force" in the litigation.

Hayes' wife, Thi-Ly, still lives in the family home, but did not respond to interview requests.

Joe Cook was not close to Peter Hayes, but he does recall their last encounter. "The last time I saw him I was up at the hospital, he was up at the hospital," Cook recalls. "I was on oxygen, and I was surprised to see him on oxygen."

Crudely Put

Crude oil is composed of numerous chemicals, many of which can be harmful to touch and to breathe. According to a Utah Department of Health fact sheet released shortly after the spill, of all the components of crude oil, VOC's were of special concern. Chemical compounds in crude oil, the fact sheet notes, can maintain levels up to 10 times higher indoors than outdoors, and several of them—including benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene and naphthalene—can be hazardous.

Although exposure to any of these chemicals is unhealthy, linking any of the health problems of residents living around Red Butte Creek to the spill is difficult, if not impossible.

A lack of definitive causation, however, does little to allay concerns of residents who believe that their health problems were caused by the spill. And even residents like Annie Payne, who remains in good health, worries for herself and her children. From Payne's backyard, a chain-link fence separates a steep slope from the creek below. Before the spill, Payne says she let her children pass freely through the fence to play near the creek. But to this day, the creek remains off-limits.

"I continue to worry," she says. "Every time my daughter throws up, I think, 'Oh, my goodness, it's leukemia.' I am super, hyper-vigilant about childhood cancers. I know my kids have been exposed to this terrible thing."

On Sept. 9, 2015, six days before Peter died, the Salt Lake County Health Department placed door hangers with information about its cancer incidence study at the 190 homes along the creek. The main thrust of the information noted that a cancer study had taken place and only one type of cancer—ovarian—was elevated in the area. Ovarian cancer, the study noted, is not known to be associated with exposure to crude oil.

Nathan LaCross, an epidemiologist with the Utah Department of Health, says that it's "very understandable" that residents remain concerned about their exposure to crude oil. And because cancer is often slow to develop, the health department plans to continue to do an update on the cancer study every five years to see if any clusters emerge.

LaCross says that although exposure to crude oil components has been linked to other types of cancer, including lung cancer, esophageal cancer and blood cancers like leukemia, none of these have been found to be elevated among those living around Red Butte Creek.

Payne says she believes the door hanger, coming as it did in the days before Peter's death, was timed as a diversion to take the neighborhood's mind off the fact that its biggest cheerleader was running out of oxygen.

"Peter, who was in the prime of his life, who was one of the more fit people I know, just went down," she says.

Origins: Peter Hayes

From the lips of his colleagues, family members and friends, Peter Hayes' life was manufactured of the stuff that makes everyone else's seem boring.

Hayes' father, Ron Hayes, was an actor, appearing in several films and television series, including The Everglades, in which he starred as a law-enforcement officer patrolling wilderness areas around Florida by boat. But Ron Hayes was also a river man who had inherited from his own father, Sam Hayes, the blood of a natural-born protester.

During a teachers' strike in Los Angeles, Heidi Hayes says she and her brother were pulled from school to march in support of the teachers. Ron Hayes, Heidi says, was the honorary mayor of Sylmar, the small California town where Peter, Heidi and their sister, Vanessa, grew up. But when Ron Hayes put up a lawn sign in support of the town's first black mayor, his honorary mayor status was swiftly revoked.

"That is the venue in which Peter grew up," says Heidi, who, like her brother, is a science teacher, and president of her local teachers' union in California. "We're kind of that way; we speak up."

But Peter's life took a drastic turn, whether he knew it then or not, when his father, in the early 1960s accompanied legendary Grand Canyon boatman Martin Litton on a river trip. At its conclusion, Litton gave Ron an order of sorts. "He said, 'Ron, if you want to go on another trip, you've got to get a boat,'" Heidi remembers. "So my dad went on the next trip in [his own] dory."

With his college friend, Ron started a business, Wilderness World, which operated rafting trips on the Grand Canyon.

When Ron wanted to expand the business north on Oregon's Rogue River, he sent Peter and a friend, both barely out of high school, to start running trips. "From a very young age, [Peter] took a leadership position, which was Peter's way," Heidi says.

Peter stayed working on the river, eventually moving to Idaho to work for Steve Lentz, who owns Far and Away Adventures in Sun Valley.

For Lentz, Peter was a lead guide, the kind of person, he says, that "you were just proud to stand side by side with, not only because of his abilities, but the process in which he guided people."

When the actor Tom Hanks called Lentz to book a trip down the Middle Fork of the Salmon River, Lentz says he summoned Peter, who a few years earlier had retired from professional boating. "Their request was, 'We really want to come out of this river trip with the full experience, with everything we can get,' and so Peter was their guide," Lentz says.

Because of his summers on the river and winters on the mountain (he was a ski patroller at Bear Valley, Calif., for several years), Peter started college in his mid 20s, says Rob Wilson, a colleague who took over Peter's ninth-grade biology classes at Rowland Hall.

The two taught together between 2005-13, and Wilson says he considered Peter a friend and a mentor.

Peter, Wilson says, would have likely been an actor had the river not so thoroughly enchanted him. But in the classroom, Peter found a stage. "He had this stage prop—an 1800s-style waxed mustache," Wilson says. "So he didn't go into acting because he couldn't study acting and audition if he was out on the river, and he chose to be out on the river."

Wilson says Peter was the rare teacher who inspired his students at a deep level, loving them almost like he loved his own son.

Like all great mentors, though, Wilson says that while much of what Peter taught him was useful, some of the time, Peter showed in his own way how to not do things. In other words, Wilson says he was like anyone else: fallible, and, at times, stubborn to a fault.

Peter also had bad feet, the result of shattering both of his heel bones during a nasty rock climbing fall in 1987. Wilson says he still has the inch-deep rubber cushion that Peter stood on while scribbling on the chalkboard.

The pain from his feet, Wilson says, was never broadcast, but he could tell that it bothered Peter, as an achy tooth would bother a bear.

"It created a little bit of a dangerous element to his emotional life, but pain does that," Wilson says. "And he took that combativeness right to Chevron. Those guys at Chevron had to have known him by the end of the day. 'Oh, OK, it's Peter Hayes, he's not going away.' And it's a shame that he couldn't have chastised them for longer."

Wilson remembers that it was January 2013, just after winter break, when Peter told him he'd been diagnosed with a terminal illness. Peter taught to the end of that term, resigning because his doctors said being around children increased risks of infection.

Wilson, like Hayes, is a pragmatic scientist. During an interview, he spoke of hypotheses deriving from specific mechanisms and diagnosable symptoms that all must be tabulated and recorded in order to ever draw a line from the oil spill to Peter's lungs. "It may or may not have contributed to his disease. I don't have enough evidence to say one way or the other," Wilson says.

But for Peter, Wilson says, there was never any doubt. And for a man like Peter, with death knocking at the door, only one mind matters.

"He believed it," Wilson says. "And that's the right word—he believed it."

Learning Is Work

Peter Hayes, or Mr. Hayes as the students that passed through his classroom knew him, had a motto: Learning is work. These words are the first one sees upon entering the Eccles Library at Rowland Hall. Taking up a large portion of the wall above the reference section is a painting by Mr. Hayes, who in addition to being a father, husband, river guide and educator, was an artist.

From a distance, the painting appears to be little more than a few sketches of students in various poses of study. A closer look reveals a series of intricate words and letters, including rows and rows of carefully crafted A, A, A-, B, B, C+.

These letters and words, says Doug Wortham, who has taught French at Rowland Hall for 38 years, and often helped Hayes keep his temper in check before the school's administration, are the grades and notes that Hayes recorded for every single one of his students.

When all of the school's teachers jettisoned leather-bound grade books in favor of Internet grade books, Hayes followed suit, but Wortham says he never stopped doing things the old-fashioned way "just in case things failed online."

Peter created the art piece, Wortham says, shortly after his diagnosis. Peter began by removing every page from every grade book and made it the background. "So, this is a real work, not just of art, but also history," Wortham says. "If you had the time and if you were one of his students, you could climb up there and find your name and all of your grades during that year."

Another large art piece from Mr. Hayes hangs over the fiction section. It is an abstract weave of colors, golds, reds, whites and blacks all splayed out on canvas.

This piece is more reflective, Wortham says, of Peter's larger body of work. But as his dying day became less abstract, so too did the artwork that he sought to leave behind.

"This isn't abstract at all," Wortham says of the "Learning Is Work" piece. "It's the absolute opposite, but death in his case was not abstract. It was looming, it was coming, there was no way out. He wanted to do something solid, stable, that didn't require almost any interpretation."

Anyone who has ever learned anything can see the truth in Peter's motto. And, according to Salt Lake City's Niermeyer, much was learned from the Red Butte Creek oil spill.

Niermeyer says Salt Lake City made strides in working with federal regulators to improve the oil-spill response time. If a discrepancy is recognized at the refinery, Niermeyer says, the policy now requires Chevron Pipe Line Co. to immediately take steps to shut down the pipeline rather than simply sending workers to scope it out. Had this occurred in 2010, Niermeyer says, oil still would have spilled, just not as much.

Some of the money Chevron Pipe Line Co. spent after the spill included the installation of fake beaver ponds in Parley's Creek, which the pipeline crosses and which provides drinking water for around 200,000 people.

An exposed portion of the pipe in the Provo River near Woodland was lowered and covered to prevent a rock from bashing into it and rupturing it, which could spoil drinking water supplies for more than a million Utahns.

Niermeyer says there is now oil-spill response equipment, including boats at Jordanelle Reservoir, booms and absorbent materials, along the Provo River and Parley's Creek in case of a spill.

A second valve was installed on the south side of Red Butte Creek. Many of the vales along the pipeline can now be controlled remotely by satellite, in case of a natural disaster that knocks out the power.

"I think we've been pretty good in using the leaks to work with the oil companies, and they've been pretty responsive," Niermeyer says. "If there is another leak, for whatever cause, we have a better way of controlling it more quickly before it spreads."

But Niermeyer remains haunted by a few inconvenient realities surrounding the pipeline, and any future lines that might be built, as one was recently proposed to follow the same path as Chevron's line.

Chevron's pipeline crosses and runs parallel to the Wasatch faultline, and many experts say the Wasatch Front is due for a hearty earthquake. The pipeline also runs near much of the Salt Lake Valley's medical infrastructure at the University of Utah.

Where the nightmare of an earthquake and broken water and sewer lines have previously occupied Niermeyer's thoughts, he now also imagines how the Salt Lake Valley would look in the aftermath of an earthquake with a massive oil spill on its hands.

In normal operation, though, Niermeyer says the pipeline has caused little fuss to Salt Lakers during the majority of its existence. And as Niermeyer and incident reports note, the cause of the spill, an errantly placed fencepost that went undetected for decades, was 100 percent avoidable.

But the June 2010 spill was but one of two incidents at Red Butte Creek that year.

A second spill occurred on Dec. 1, and once again, federal regulators say the cause was failure by Chevron to follow protocol. Before the pipeline was back up and running in June (it was functioning nine days after the spill), Niermeyer says federal regulators had Chevron pressure test the section that runs beneath Red Butte Creek. Dyed water was injected into the pipe to help spot any leaks. The test went off without any hitches.

But in December, as cold weather set in, Chevron shut the pipeline down to run another test. When the company resumed pumping crude, a valve burst near the creek, spewing crude into the company's new containment area. The oil eventually overtook the containment area, and flowed to within a foot of the creek before it was stopped.

According to a corrective-action order from PHMSA, after the dye test, Chevron Pipeline officials failed to purge all of the valves to ensure that no residual water remained. "The preliminary findings indicate that the failure to remove all of the test fluid (water) used during the June 2010 hydrostatic pressure test or to take appropriate action to ensure that any remaining water would not adversely affect the operation of the Number 2 Line may have caused or contributed to the December 2010 spill," the PHMSA order states.

Ken Robertson, a policy, government and public affairs expert at Chevron, defends the pipeline company, saying that Chevron cleaned up after itself, and that all of the work it performed was done under the direction and approval of the EPA, Utah's DEQ, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake County and the Utah Department of Health.

"Chevron Pipe Line immediately accepted responsibility for the spill, apologized to those affected and set up a claims facility to provide residents with prompt and fair compensation for property damages, personal inconvenience and other losses," Robertson said in an email.

Robertson, however, did not answer any questions about Peter Hayes or any public-health concerns resulting from the spill.

What Peter, many of his neighbors and Brian Moench, president of the group Utah Physicians for a Healthy Environment, all wanted to see was the establishment of a long-term health study, funded by Chevron.

A short time after the spill, KSL Channel 5 did a story about how Peter and others who lived near the creek were asking Chevron to create a $15-million escrow account to help pay health-care costs of affected residents.

In the story, then-Salt Lake City Mayor Ralph Becker said that he believed Chevron had met its responsibilities and a health-care fund was unnecessary. In the immediate aftermath of the spill, Becker was a vocal critic of Chevron and he vowed to hold the company accountable for damages stemming from the spill. Becker did not return calls for this story.

Not Our Responsibility

After spending its tens of millions on cleanup, Baker (with Utah's Division of Water Quality) took the lead in negotiating the penalty that Chevron Pipe Line would have to pay.

Baker's scope of responsibility, he explains, was to penalize Chevron for violating water-quality standards, and nothing else. "Our authority and the scope of our settlement was just on water-quality issues," Baker says. "They weren't on air-quality issues, they weren't really on the health aspects, other than the protection of recreational activities in the water."

Baker wrung $4.5 million out of Chevron Pipe Line for the spill, and by the time Peter Hayes took his last breath, nearly every penny had been doled out as grants for conservation and restoration projects along the creek, and other parts of the watershed.

Since it wasn't Baker's responsibility to advocate for health-care studies, even though he was at the table negotiating a settlement with Chevron, it's fair to ask whom Peter Hayes should have petitioned to establish such a fund.

The answer, Baker says, would have been for affected residents to sue Chevron. "We just didn't think it was our responsibility to do that," Baker says, of hitting Chevron up to establish a health-care fund. "If there was a case that could be proved that Chevron had caused health effects to a lot of people, or a group of people, then I think that should have been pursued civilly.”

Rowland Hall biology teacher Wilson says that Peter knew and loathed the fact that disenfranchised people the world over had to fight corporations for justice when environmental accidents occurred. Within days after the spill, Wilson says, Peter had compiled a list of instances where pipelines had burst around the world, often in impoverished areas. One big difference separated Peter from the many other individuals, families and towns where pipeline accidents caused mayhem: Peter, by every definition of the word, was not disenfranchised.

"Pete's neighborhood is different, it's a nice neighborhood," Wilson says. "Those are voices that get heard. You could say we're represented. We're enfranchised, that neighborhood. Not so well when it came to the spill."

A Voice Stolen

Moench, of Physicians for a Healthy Environment, came to know Peter through the spill, and he says that it's clear that the proximity of Peter's home to the creek exposed the Hayes family to "significant concentrations of VOCs."

The question of whether or not Peter's disease was caused by the spill is partially answered, he believes, by a study that analyzed fishermen who helped clean up an oil spill off the coast of Spain. The workers, Moench says, showed signs two years after their exposure of inflammation in the lungs and chromosomal damage to white blood cells, which increases the risk of cancer.

"If you look at that information and apply it to Peter's situation, it is very plausible that Peter's lung injury could have been triggered by the VOCs he was exposed to," Moench says.

But Moench, like Wilson, says the problem with pollution is that it's never easy to "pin a toe tag" on a foot at the morgue and say "pollution did this."

"In my mind, [Peter's disease] pretty well implicates his exposure, but it certainly doesn't prove it," he says.

On the day of the spill, Moench says he believes residents should have been evacuated. Certainly, he says, any residents with young families or pregnant women should have been put on notice. And any settlement lacking money for health studies [none of the money used by the Utah Department of Health on the cancer incidence reports came from the settlement. LaCross says it's all taxpayer money] is, in Moench's opinion, "unsatisfactory."

"The idea that a settlement was reached where there really wasn't any money to study these people or to help them with the health-care consequences, that to me sounds like a poor settlement," he says.

Peter is gone, but his vocal opinions, his refusal to quit and his ideas have been pounded into the minds of many who met him. Baker at the Utah Division of Water Quality immediately recognized the name of Peter Hayes. Niermeyer, too, even knew that Peter had passed away.

Peter mentored Wilson, who might well end up teaching more ninth-grade biology students than Peter did. And Wortham, the French teacher, says that Peter's visionary opinions on education, whether well received by his bosses during his life or not, have all managed to come to fruition after this death.

Chevron's oil pipeline, though, was put into the ground three years before Peter was born. It pumped oil to the refinery all those days Peter spent on the river. The pipeline's steel is a tireless, ominous and mysterious resident of this community. It outlived Peter, and in the opinion of many, it silenced a man who was good at being heard.

"He had a voice worth hearing," Wilson says. "He had a voice that wanted to be heard. He had a loud voice, and it was quite literally silenced by the fibrosis. He was running out of breath."

But that desire to speak out, Wilson says, is something that Peter passed down to his students, his family and his friends. It is this legacy, Wilson says, that Peter should be remembered by. Not his brief time sparring with Chevron.

"The desire for speaking up for yourself, speaking up for the little guy," Wilson says. "That's part of the legacy he left with people he touched before any of this happened."