Beneath the Surface: A River Runs Through It

Authored by Amy Choate-Nielsen

Source: The University of Utah Magazine

University of Utah students bring three creeks to life at the Three Creeks Confluence. This article highlights how water can help our communities.

Unearthing streams breathes life back into local communities.

The journey of a single drop of water falling from the sky onto the Wasatch Mountains is predetermined. After it careens toward the granite rocks and pine trees below, it will head west to the Jordan River, and then to the Great Salt Lake—but the path isn’t easy.

In the beginning, water flowing from the peaks surrounding this desert city will find itself divided into seven canyons etching horizontal lines across the valley to the river in the distance. From a bird’s-eye view looking north to south, the creeks flow through City, Red Butte, Emigration, Parleys, Mill, Big Cottonwood, and Little Cottonwood canyons like organized veins, pumping life from the east to the west—except where they are buried, hidden from view. There, you see parking lots, houses, and pavement.

After the water leaves its beautiful canyon, it quickly dives underground, flowing through pipes and culverts. It does not see the light of day.

And that’s where Brian Tonetti BS’14 comes in. As the executive director of the Seven Canyons Trust, Tonetti is making it his life’s work to unearth those streams, one inch at a time. His vision started at the U, where he joined 20 classmates in an Urban Ecology capstone class in the Department of City and Metropolitan Planning and sought to create a plan to daylight the valley’s seven creeks. In that course, Tonetti and his peers identified one key place to begin: the three creeks confluence. This is where the Red Butte, Emigration, and Parleys streams combine and join the Jordan River.

It’s where Tonetti is standing now, with his commuter bike leaning against a construction fence. As he looks up 1300 South, the road under which the water flows, he can see all the way to the canyons where these creeks began. He’s come a long way, but he still has far to go.

“My whole career has been working toward this,” Tonetti says, watching a muskrat dive into the water that used to be covered with concrete. “You can bring people here and say, looking at this site, it is possible. Looking around, you can see the impact students can have. This site is a case study in optimism.”

Daylighting Streams

The Three Creeks Confluence Park marks a milestone in Salt Lake City’s history. It is the second daylighting project to be completed here. The first was completed in 1995, when Stephen Goldsmith, who taught Tonetti’s capstone class, and landscape architect Jan Striefel MS’85 worked with the city to bring a half-mile of City Creek out of its culvert, up to the surface. The city removed a parking lot to create a park around the now-exposed waterway, just west of Memory Grove, where the sound of birds percolate through the air and wildlife has returned.

“I don’t look back on the work and say, ‘Wow, look what we’ve done,’ but acknowledge the privilege of doing this work and hope that others will say, ‘Now, what can I do?’ ” Goldsmith says of the project.

Goldsmith’s experience as the former planning director of Salt Lake City and Loeb Fellow at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design led him to want to teach a capstone course that would ask students to plan a way to daylight the seven creeks that run through Salt Lake to the Jordan River. He asked for a 100-year visioning document.

Once the students completed the document and received an American Planning Association award for their ideas, they didn’t want to stop. They looked at examples of daylighting all around the globe—from the Cheonggyecheon Stream in Seoul, South Korea, to the Wadi Hanifa Stream in Saudi Arabia and the Saw Mill River in New York—and they decided to keep going and form a nonprofit organization that would use their document as its guiding star.

“Daylighting is happening all over the world because people realize we need access to water, not only because we need it to live, but to aid our spirits,” Goldsmith says. “A restoration project doesn’t just restore the waterway, or the neighborhood, but enlivens the human spirit.”

Open rivers and streams also add value to communities, says Megan Townsend BS’15 MCP’17, community and economic development director of the Wasatch Front Regional Council and a former capstone student of Goldsmith’s.

Exposing streams where possible is an expensive undertaking, but so, too, is maintaining underground waterways and replacing pipes. Allowing water to flow freely through soil, grass, and sand purifies it and removes contaminants and lets excess moisture absorb into the land, instead of being forced to the surface when grates and culverts become overwhelmed, Townsend says.

With that in mind, Tonetti and his classmates formed a plan to take their vision to the next level—and they approached then-Salt Lake City Councilman Kyle LaMalfa BS’98 BS’05 MStat’09 with their idea.

Fording the Future

LaMalfa loves Salt Lake City, and he loves nature. He wants his future grandchildren to have a piece of wilderness close by, no matter where they may live in Salt Lake County. So, when Tonetti reached out six years ago with an idea that combined those two loves, LaMalfa was intrigued. He wasn’t deterred by the fact that the idea was coming from college students, or that it was step one of a 100-year plan. He was willing to get moving.

“As a council member, every day you work with something that is going to happen in 25 years,” LaMalfa says. “And if something takes 100 years to realize, even though I’m not going to be alive to see the dream come true, I can see where my contribution fits in.”

Having LaMalfa’s support was a huge win for Tonetti’s team. After that, the city approved the project and provided grant money to start purchasing land. Little by little, the vision crystalized and took on a life of its own.

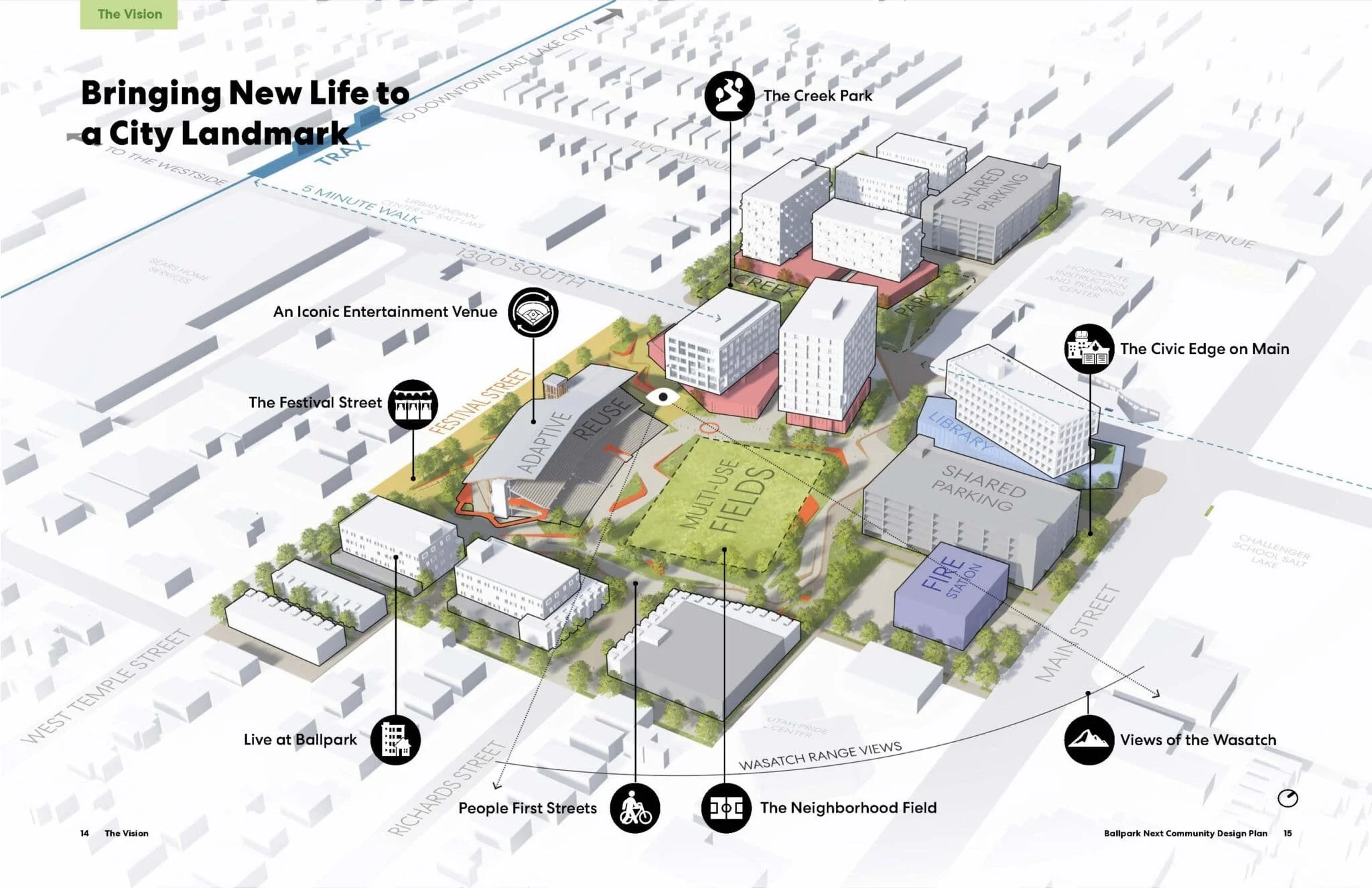

“The initial construction project was supposed to be $500,000 but it became clear that the community really wanted to uncover the streams entirely and create a much larger park than we initially planned,” says Salt Lake City Parks and Public Lands Project Coordinator Tyler Murdock BS’10 MPP’16. The cost grew to about $3 million for the park, which includes a children’s play area, sitting and walking spaces, and a new canoe takeout.

Making the leap from hoping to make a difference in the waterways in Salt Lake County to seeing it become reality has been a slow but tangible process, and every step along the way is worth it, Townsend says. As she explains it, daylighting is a phrase that can literally mean exposing a stream to the sky, but it can also mean knowing there is water flowing beneath your feet, below the floor, under the concrete.

“Sure, daylighting a creek is measurable progress, but so is public education and bringing children out to see creeks that they didn’t know were there,” Townsend says. “The vision isn’t just about what’s in the ground, it’s also about awareness.”

Urban Acupuncture

As Tonetti walks the grounds of the new park, he points out the significance of its surroundings. Across the street is a free preschool program for low-income children. Around the back is a community center. The wide opening with a view straight to the mountains used to be a little dirt road. But now it’s a place children and youth can come and watch the ducks putter around on the bank of the Jordan River.

Only 200 feet of the creeks were cracked open here. But it’s a start, and it will make a difference, Goldsmith says.

“Little bits of urban acupuncture like this, little pinpricks of change, have a global impact because they inspire other communities to say, ‘We can do this. If they can do that in Utah, we can do that here in Taiwan,’ ” Goldsmith says. “It’s hopeful work.”

All seven creeks from the mountains just east of Salt Lake City flow toward the Jordan River.

The fact that this “urban acupuncture” in Salt Lake City was initially the brainchild of college students is a benefit to inspire young people everywhere, says Chelsea Gauthier BS’10 MCMP’13, board member of Seven Canyons Trust and associate director of Center for the Living City, a New York-based global urbanist organization.

“With projects like this, how it started—with students researching and making the invisible visible—they help spur the ‘just do it’ approach and not get this analysis paralysis that happens a lot with big planning initiatives,” Gauthier says. “Three Creeks is showing the world that your ideas matter, and anyone can be part of change.”

For the Glendale neighborhood where the park now sits, this kind of change can breathe new energy into the community, Murdock says.

“Within Salt Lake County, this project will be an example of how you can take hidden or ignored space within our communities and transform it into a space that is an asset, where the community wants to be,” he adds.

And one day, it’s possible that others who dream of a sustainable world where humans and nature coexist peacefully may encounter the Three Creeks Confluence Park and be inspired to take their own first steps in a 100-year journey. Perhaps the optimistic ambition of college students will be contagious.

“When you think about this project, we were just students,” Tonetti says. “We didn’t really know what we were doing, and I think, in a certain respect, our naivete helped us, just going to a council member and saying, ‘Hey, what do you think about this idea?’ ”

That is how the journey of a single idea begins—and, after traveling through twists and bends, ends with a new community gathering place, a park, and a vision of what’s possible for the future.